| Ballet |

1 |

B1 |

B001 |

Fancy Free |

|

Leonard Bernstein |

Fancy Free |

May 4, 1944 |

|

By Leonard Bernstein (Fancy Free, 1944). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

Oliver Smith |

Kermit Love |

Peter Lawrence |

|

|

|

|

1,944 |

April 18, 1944 |

|

Metropolitan Opera House |

New York City |

April 18, 1944, Metropolitan Opera House, New York City. |

Ballet Theatre |

|

In the repertory: continuously, since the premiere. |

Ballet Theatre. In the repertory: continuously, since the premiere. |

Harold Lang, John Kriza, Jerome Robbins (Sailors); Muriel Bentley, Janet Reed, Shirley Eckl (Passersby); Rex Cooper (Bartender). |

Leonard Bernstein |

|

|

|

Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

asdfasdf |

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

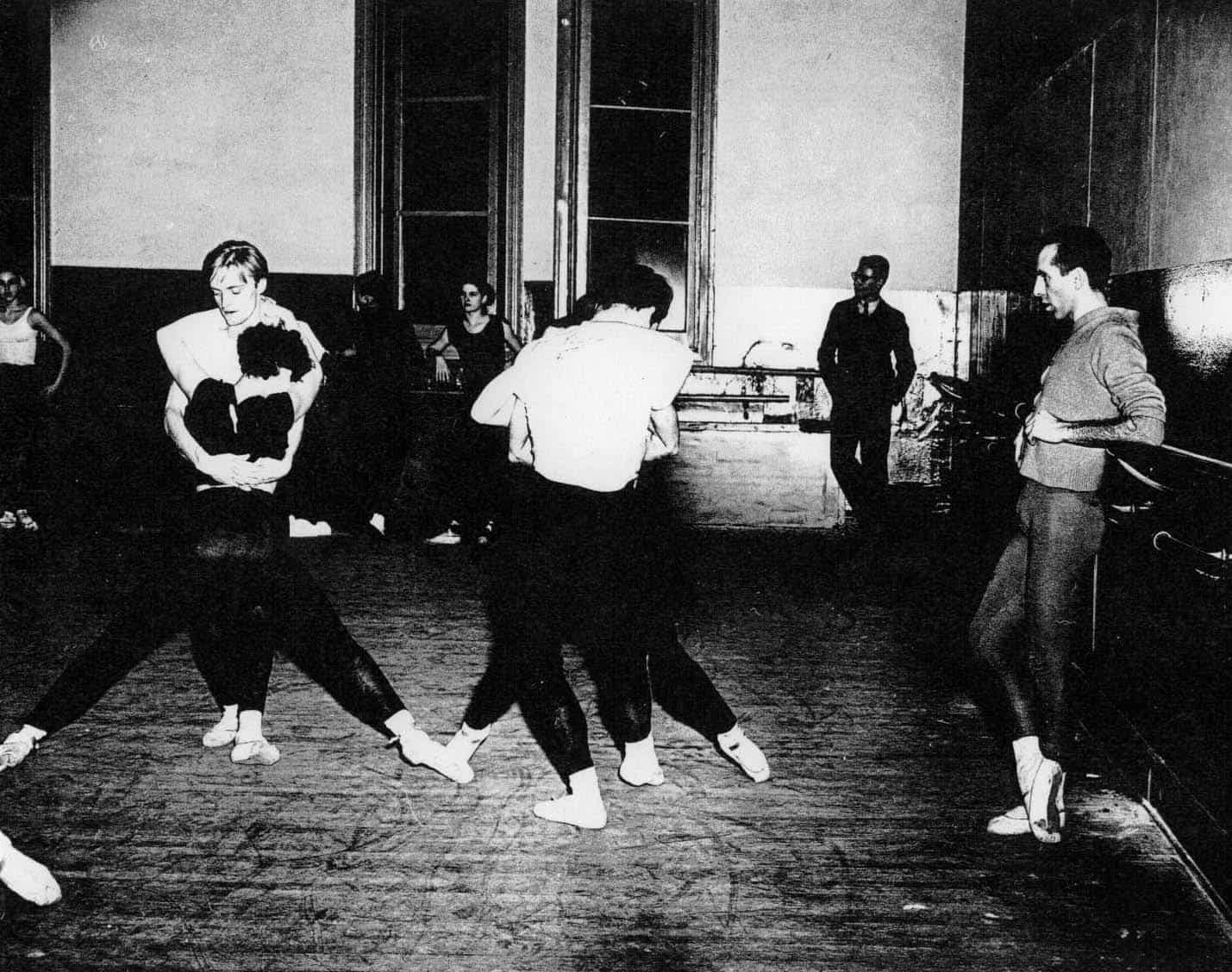

"The ballet concerns three sailors on shore leave. Time: the present, a hot summer night. Place: New York City, a side street."

|

-In the original staging, the pas de deux was danced by Janet Reed and Jerome Robbins (as the third sailor, who dances a rumba solo). When Jerome Robbins stopped performing in the ballet, John Kriza (as the easygoing second sailor) danced the the pas de deux.

-This ballet became the point of departure for the creation of the musical On the Town [M1]. |

1980, New York City Ballet; 1985, Dance Theater of Harlem; 2002, Birmingham Royal Ballet; 2003, Pennsylvania Ballet; 2004, Royal Danish Ballet, Tulsa Ballet; 2005, Miami City Ballet; 2006, Pacific Northwest Ballet; 2007, San Francisco Ballet.

|

|

Jerome Robbins (Christian Science Monitor, May 13, 1944):

"After seeing Paul Cadmus’ painting, ‘The Fleet’s In,’ which I inwardly rejected though it gave me the idea of doing the ballet, I watched sailors, and girls too, all over town. The gestures are taken from life. Of course they are blown up, theatricalized, but they are based on human values....One thing I wanted to show was good, healthy American energy and vitality, to prove that dancing doesn’t have to be Russian to be strong and vigorous. Not that I have anything against Russians–I’m all for them. It is only that I think American dancing is fully as good." |

Arthur V. Berger (New York Sun, April 19, 1944):

“A ballet has finally been found for those who have passionately desired something to liven up the repertory….The whole production shouts like a billboard poster. There is a sophistication among all the participants to make it evident that they are aware of the blatancy. But little is done to balance it…..Mr. Robbins has an excellent sense of continuity and timing, and he has brought out the best qualities of his cast. But Mr. Robbins has still to master certain elements of taste and imagination.” Louis Biancolli (New York World-Telegram, April 19, 1944):

“Not since Agnes De Mille’s Rodeo has an audience taken so heartily to a ballet steeped in heartwarming homespun style. Equipped with some of the freshest gifts around town, the Ballet Theater staff has turned in a real hit, pointing the way to what may still show up as a strictly native chapter in ballet annals.” Edwin Denby (New York Herald Tribune, April 19, 1944):

“Jerome Robbins’s ‘Fancy Free’ was so big a hit that the young participants all looked a little dazed as they took their bows. But besides being a smash hit, Fancy Free is a very remarkable comedy piece. Its sentiment of how people live in this country is completely intelligent and completely realistic. Its pantomime and its dances are witty, exuberant, and at every moment they feel natural….If you want to be technical you can find in the steps all sorts of references to our normal dance-hall steps, as they are done from Roseland to the Savoy.” Robert Jeans (New York Daily News, April 19, 1944):

“It’s twenty-five minutes of strictly American ballet–and when it was over, the sittees and standees rocked the Temple of Art in raucous approval….Choreographer Robbins, Harold Lang and John Kriza dance the sailor roles expertly. Equally expert are the hussies, danced by Muriel Bentley, Janet Reed and Shirley Eckl. Non-dancing Rex Cooper is perfect as the bartender. He serves the drinks and keeps his mouth shut.” John Martin (New York Times, April 19, 1944):

“To come right to the point without any ifs, ands, and buts, Jerome Robbins’ ‘Fancy Free’ is a smash hit. This is young Robbins’ first go at choreography, and the only thing he has to worry about in that direction is how in the world he is going to make his second one any better….The ballet concerns three sailors who pick up two girls and contest for the privilege of not having to be the odd man out. Each of them tries to out-dance the others, and–all of them succeed!….The whole ballet is just exactly ten degrees north of terrific.” Henry Simon (PM, April 19, 1944):

“Mr. Robbins has invested this little incident with such ingratiating toughness, such a distinctly American accent, and such infectious high spirits that the audience is constantly either snickering, applauding, or laughing outright.” Robert Coleman (New York Daily Mirror, April 23, 1944):

“Jot down Fancy Free on your list of ‘must-sees.’ It’s by all odds the best new ballet of the season. In fact it would be a stand-out in any season….Robbins is likely to have a flock of offers from Broadway’s major musical producers.” Robert A. Simon (New Yorker, April 29, 1944):

“This was the début of Mr. Bernstein as a ballet composer and also the première of Mr. Robbins as a choreographer. Both young men made it plain they knew their business. Mr. Robbins’ staging was as expert as Mr. Bernstein’s writing. The responsibilities of a choreographer didn’t interfere with Mr. Robbins’ own able dancing as one of the three sailors, and it might also be noted that the most brilliant solo turn in the ballet was one he devised for Harold Lang, who stampeded the clientele with it.” Margaret Lloyd (Christian Science Monitor, May 6, 1944):

“The action unfolds with the compactness, the singleness of purpose, of a brilliant short story. Every step and gesture counts, and moreover, it instantly understood. And it calls for, and gets some, tremendous dancing.” |

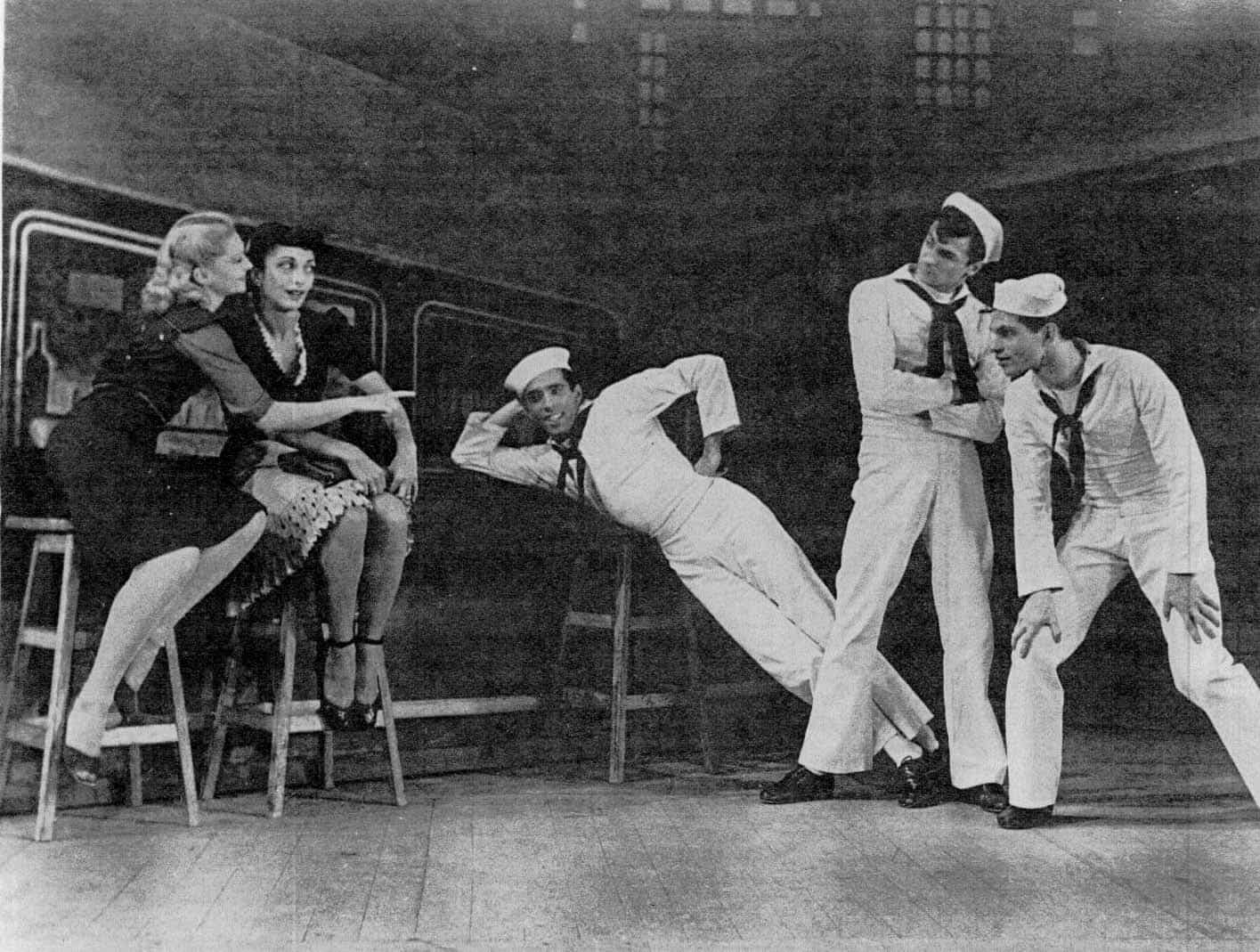

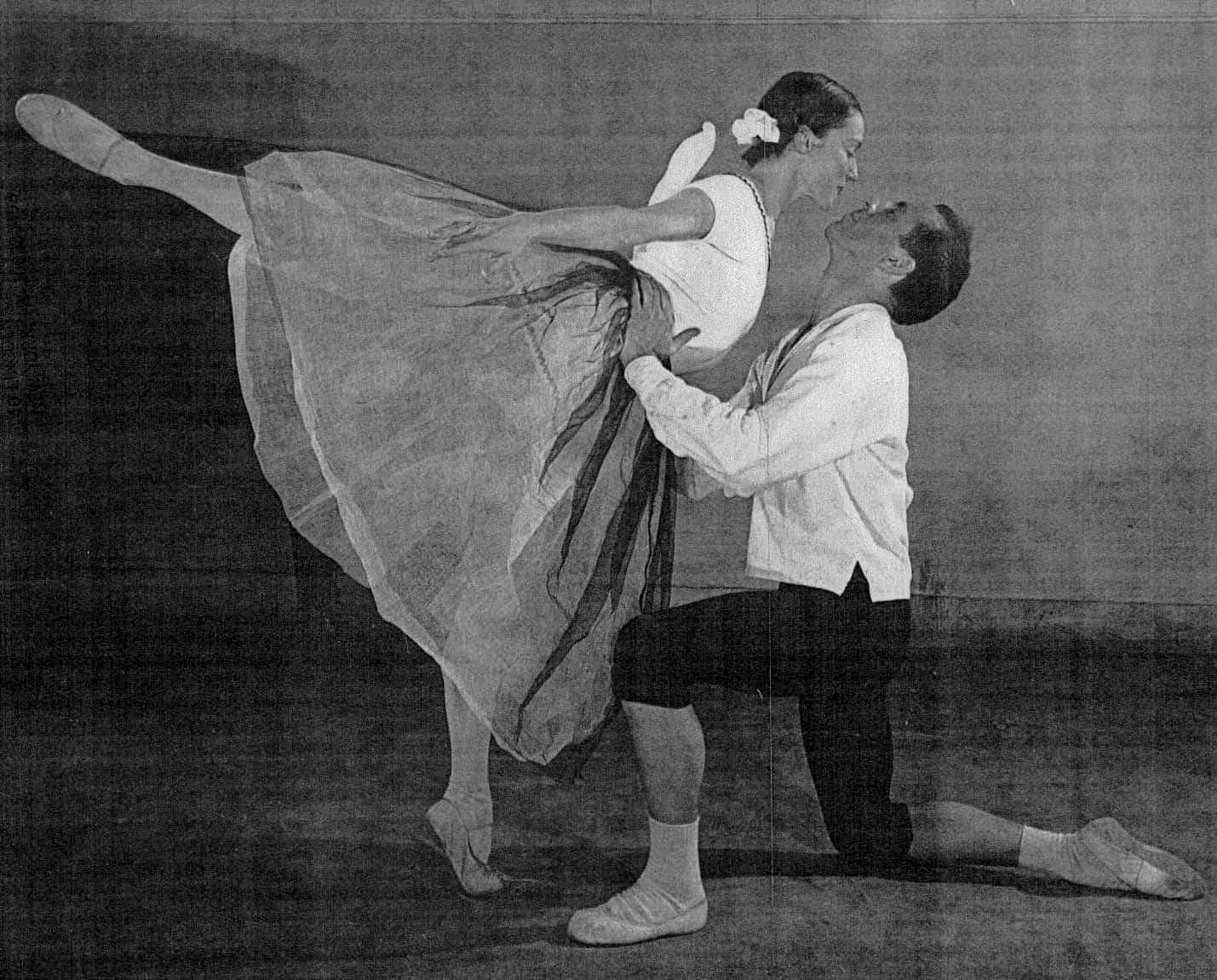

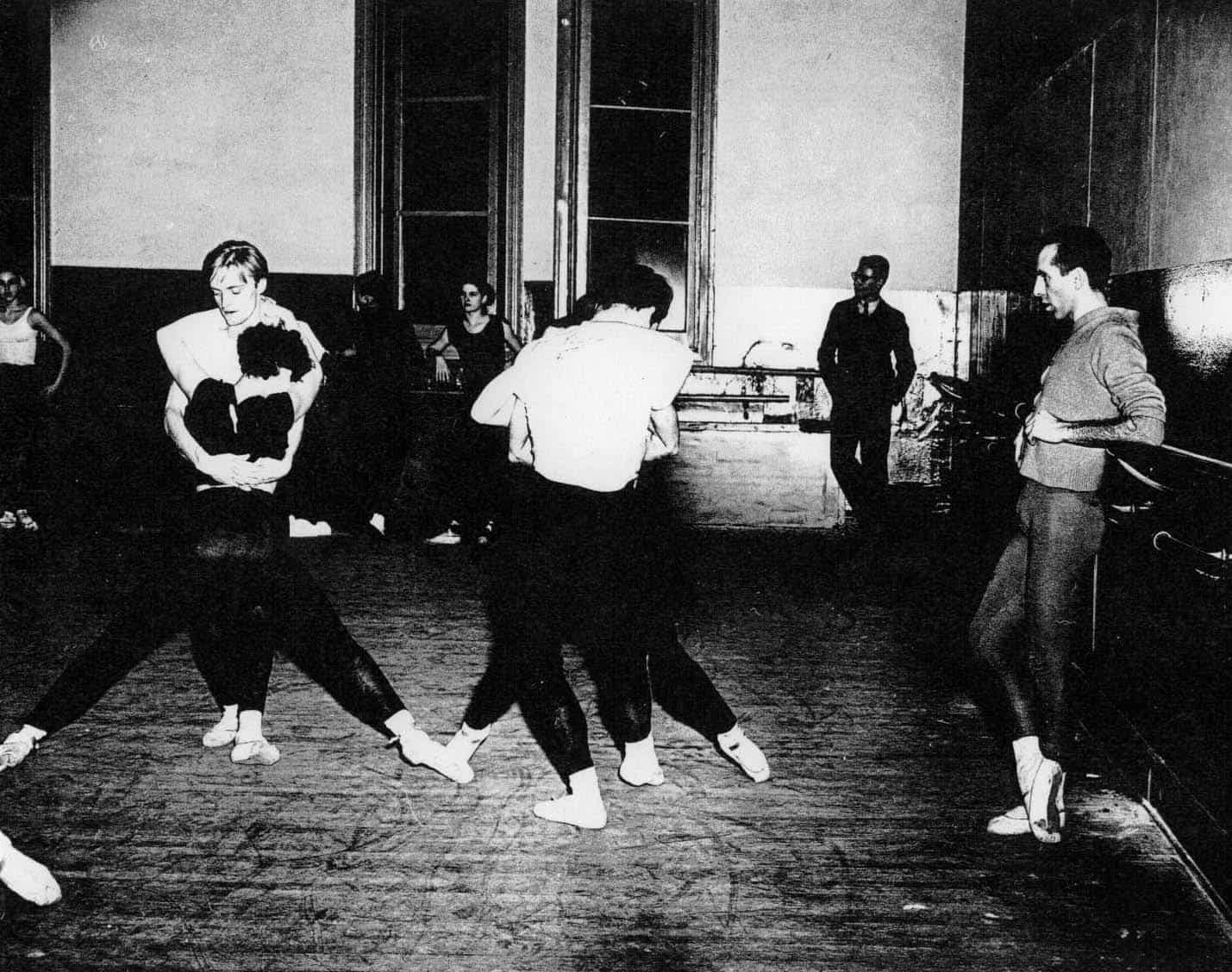

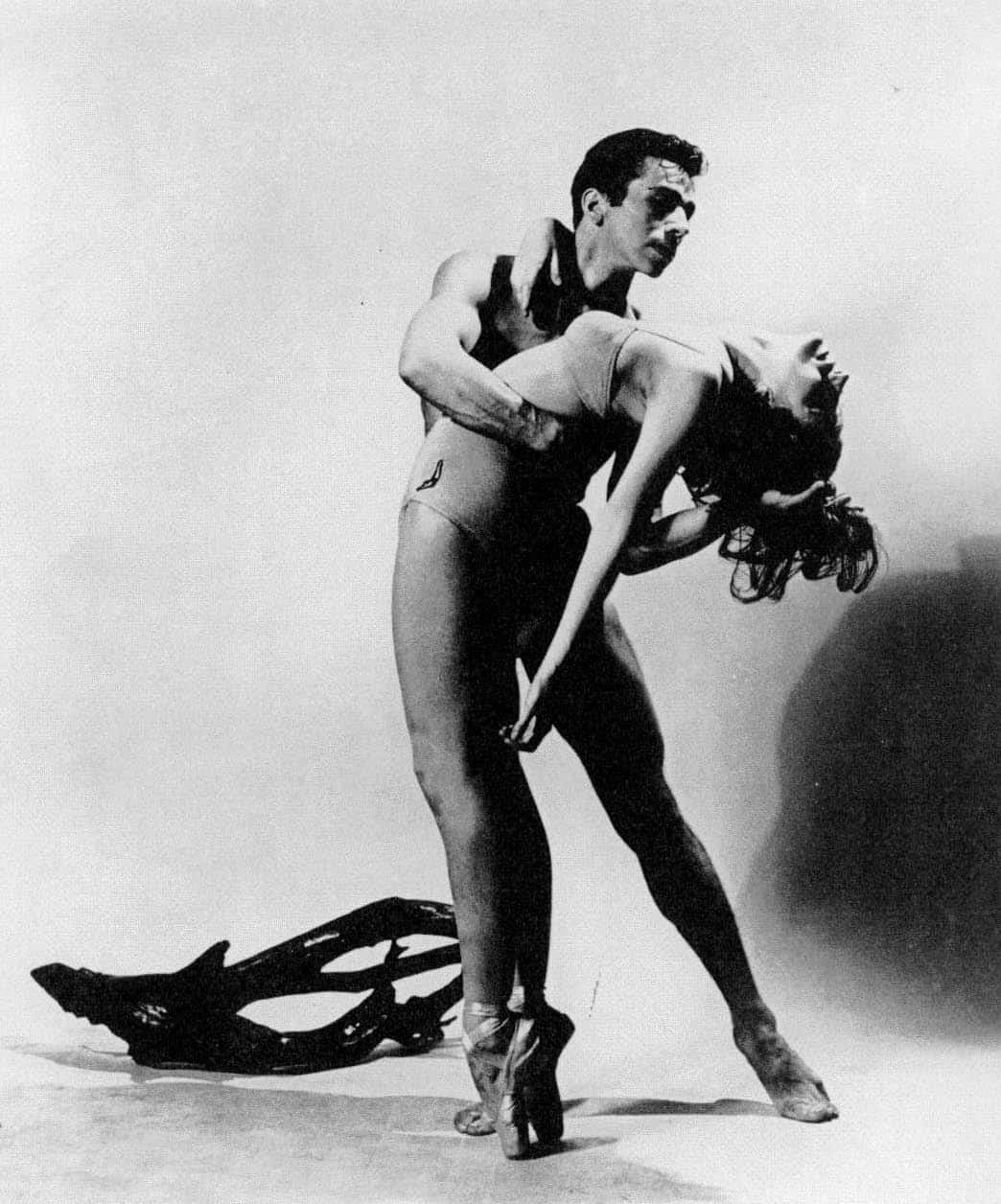

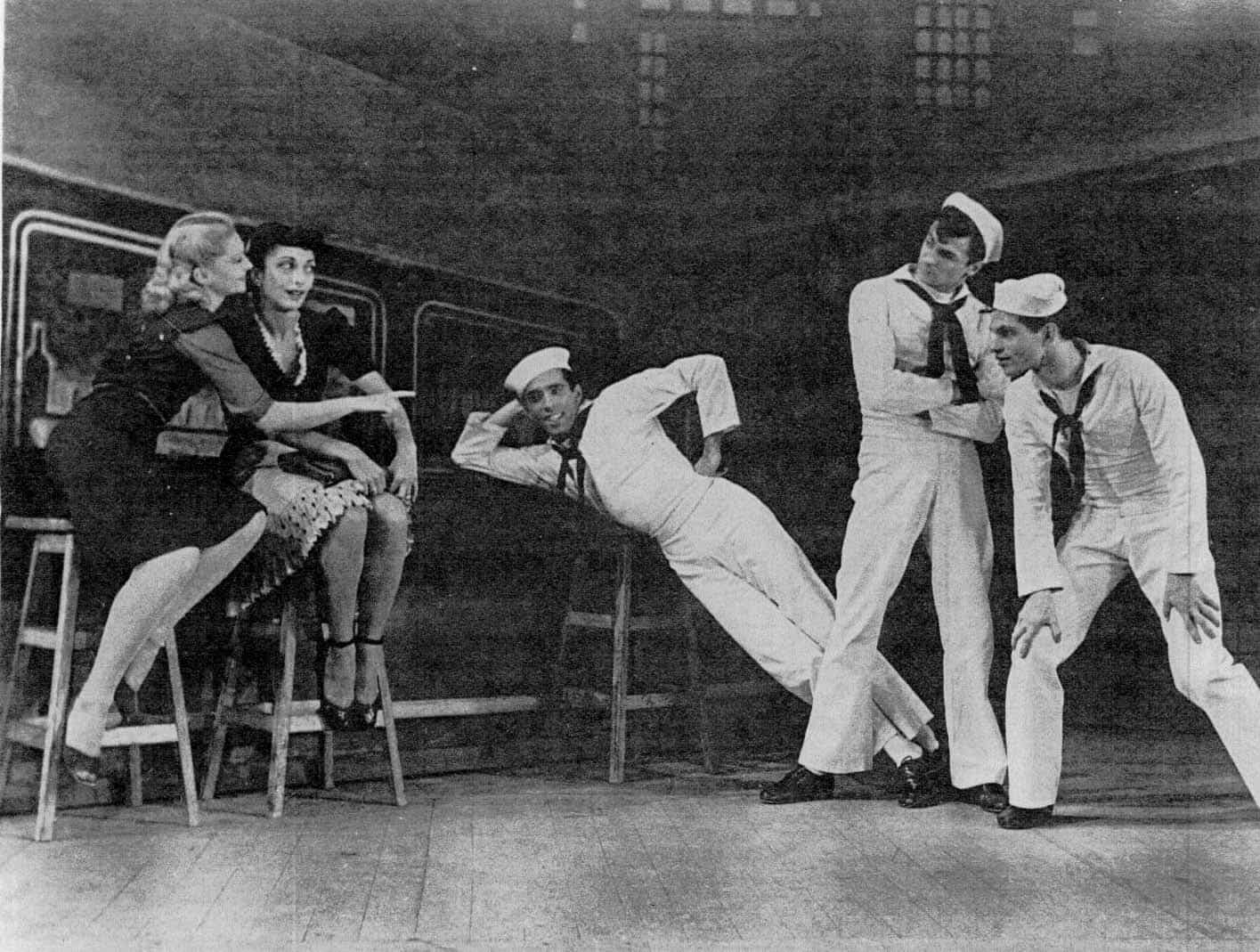

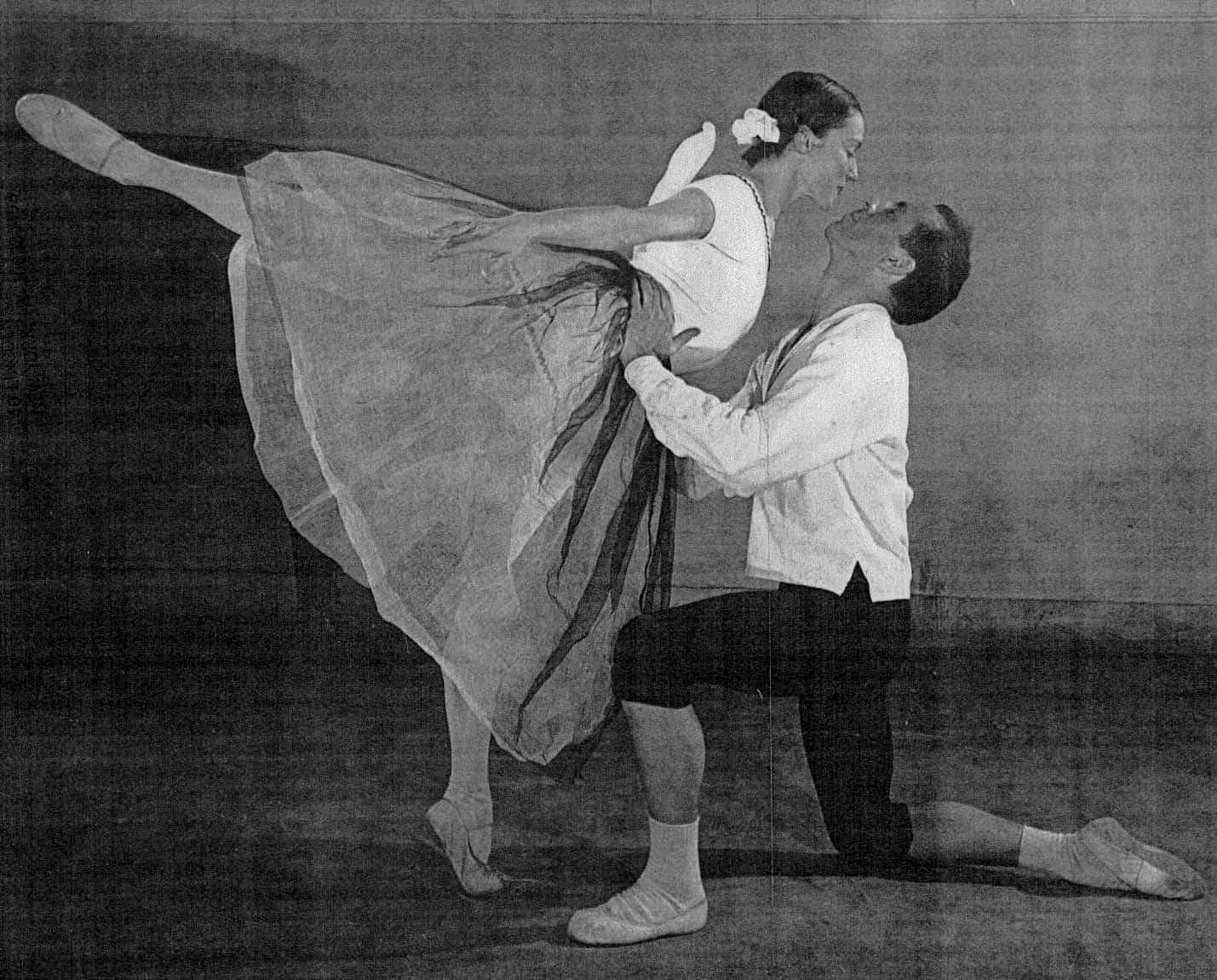

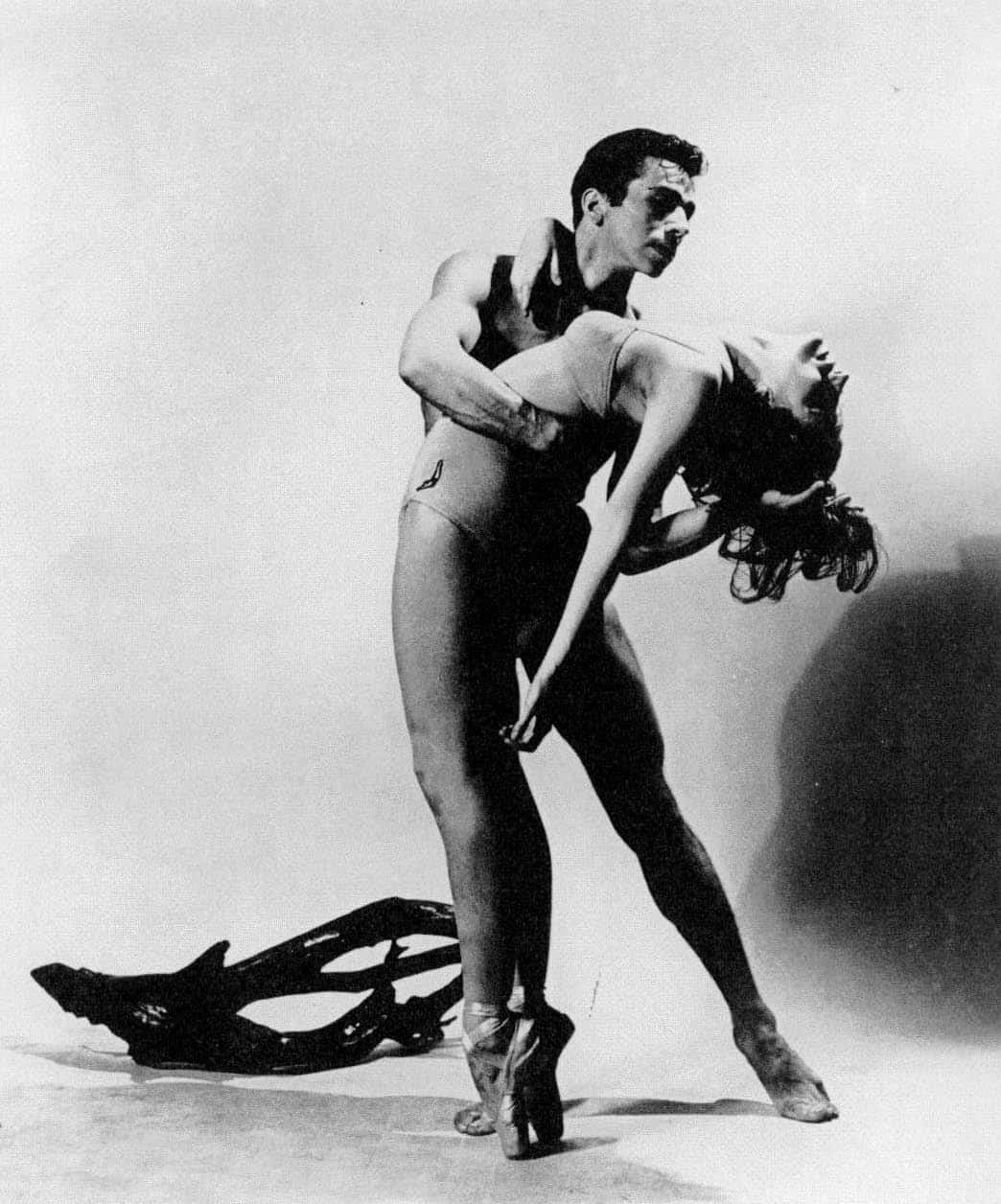

Fancy Free: Janet Reed, Muriel Bentley, Jerome Robbins, John Kriza, Harold Lang, 1944. (Fred Fehl)

|

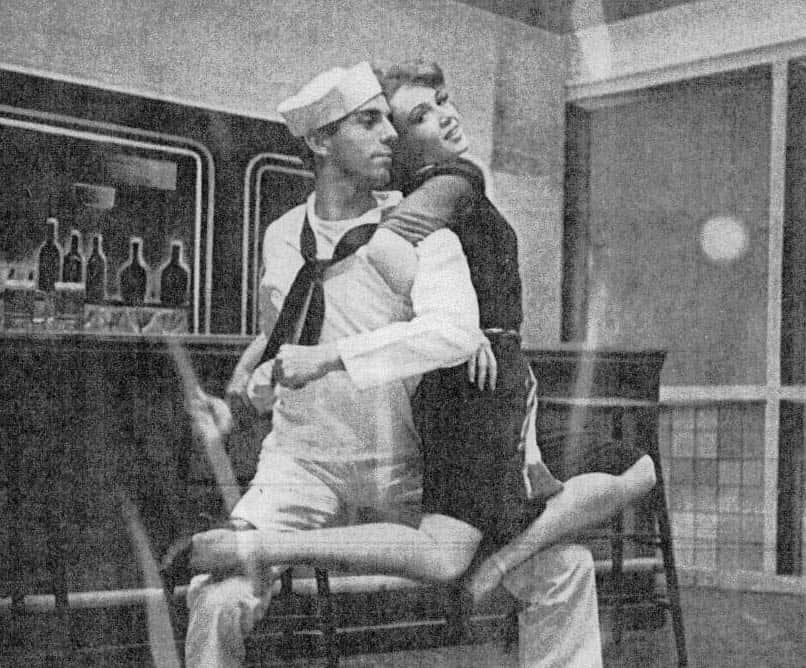

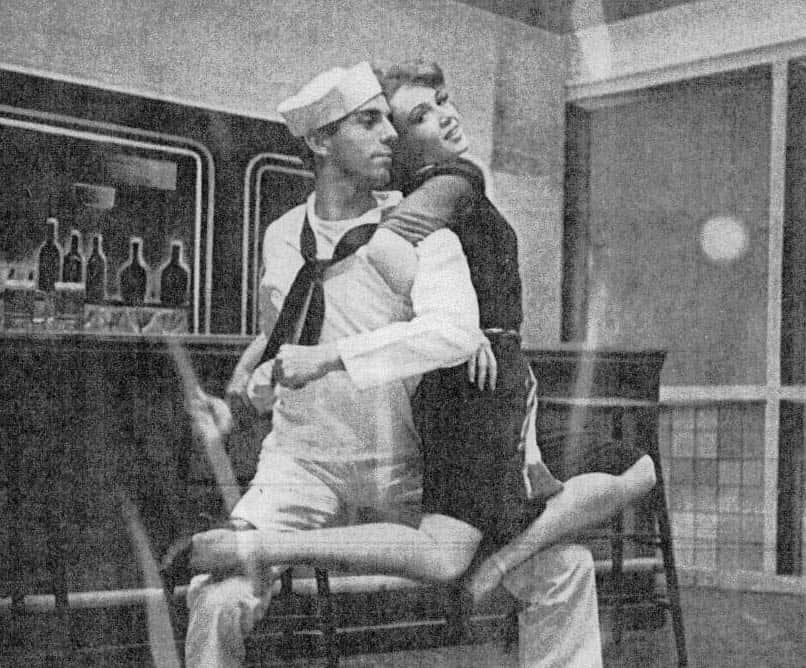

Fancy Free: Jerome Robbins, Janet Reed, 1944. (Fred Fehl)

|

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

311 |

| Ballet |

2 |

B2 |

B002 |

Interplay |

|

Morton Gould |

Interplay [original title: American Concertette] |

May 31, 1945 |

|

By Morton Gould (Interplay [original title: American Concertette], 1945). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

Oliver Smith |

Irene Sharaff |

|

Marcel Hansotte |

|

|

|

1,945 |

October 17, 1945 |

|

Metropolitan Opera House |

New York City |

October 17, 1945, Metropolitan Opera House, New York City. |

Ballet Theatre |

|

In the repertory: 1945-52, 1954-55, 1958, 1964, 1966, 1981. |

Ballet Theatre. In the repertory: 1945-52, 1954-55, 1958, 1964, 1966, 1981. |

John Kriza, Harold Lang, Tommy Rall, Fernando Alonso, Janet Reed, Mildred Herman, Muriel Bentley, Rozsika Sabo |

Morton Gould |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“A short ballet in four movements in which there is a constant play between the classic ballet steps and the contemporary spirit in which they are danced.” |

-An earlier version, minus the pas de deux, premiered on June 1, 1945, at the Ziegfeld Theatre, New York City, as part of Billy Rose’s Concert Varieties [M2].

-Beginning in 1986, the costumes used were designed by Santo Loquasto. |

1952, New York City Ballet; 1959, Ballets: U.S.A.; 1972, Joffrey Ballet; 1977, Royal Danish Ballet; 1977, Pennsylvania Ballet; 1978, School of American Ballet; 1989, San Francisco Ballet; 2001, Boston Ballet. |

|

Jerome Robbins (interviewed by Anna Kisselgoff for a New York Times article on May 21, 1990):

“I think we’d grown out of what I would call the ‘opera’ stage of ballet.” Jerome Robbins (speaking of a revival of ‘Interplay’ at the Joffrey Ballet in 1977, Playbill, November 1978):

“You don’t always get better as you get older. You change–and some things, of course, improve–but sometimes something you made when you were young is awfully good for that time.” |

Louis Biancolli (New York World-Telegram, October 18, 1945):

“From all signs, this new frolic in snappy jazz-drenched idiom is here to stay. The crowd hugged it tightly to itself last night. It’s that kind of ballet–fresh, young, zippy, with a heartwarming mood radiating joie de vivre on a mass scale….Interplay’ is part comedy and part satire, all of it in good fun….In places you’ll recognize Robbins’ Fancy Free style–the linked trios almost tripping themselves up, the slightly sardonic sweeps of gallantry, the pepped-up classicism. You’ll also find jive and toe dancing mingled here in chatty ease. Jerome Robbins is the great leveler of ballet styles.” Edwin Denby (New York Herald Tribune, October 18, 1945):

“It is a quick, playful dance suite, smoothly combining classic steps with a few athletic and jazz moments. It is juvenile in atmosphere, expert in construction, sharp in rhythm. In dance continuity it is a big step beyond Fancy Free, though in emotion it is more innocuous. Its weakness as expression is in the superficial nature of the relationships between the dancers….But this is judging the little piece by really serious standards, and it is a proof of its merit that one feels like applying serious standards to a number that seems intended only as a friendly entertainment.” John Martin (New York Times, October 18, 1945):

“Those who expect to find in Mr. Robbins’ second ballet anything like a repetition of his first, Fancy Free, are doomed to disappointment. Interplay is a pure abstraction, without story or characterizations of any kind. Indeed, the most important aspect of the work is just this: for in it the choreographer has freed himself from the danger of being typed as a composer of genre, not only in the public mind but also, no doubt in his own….He has employed the basic approach of the classic ballet and its vocabulary to make a slightly jazzy, quite contemporary, American kind of dance.” Edward O’Gorman (New York Post, October 18, 1945):

“In its revised version it is better than ever, and it was darned near tops in the first place. The set is naturally bigger and, to my taste, better, having undergone a process of simplification. As it is now, it is simple but not stark, colorful but not flashy….The ballet is a treat for the ear as well as a delight to the eye.” Robert Sylvester (New York Daily News, October 18, 1945):

“The Ballet Theatre went back to childhood games and athletics, last night, for an enormously effective and fast modern ballet called Interplay….Utilizing eight youngsters and a bare stage trimmed in spectacular orange, green, red and blue, this newest ballet item runs as fast and true as the good game which it is.” Arthur V. Berger (New York Sun, October 19, 1945):

“Jerome Robbins Interplay was like a breath of fresh air. It is what we have been waiting for from our young choreographers, a ballet which does not waste time with people standing around the stage and obvious quips that tarnish after you have seen it a few times….Anything said about ‘Interplay’ must be qualified by he statement that it is a modest effort, about ten minutes long….But it is hard to believe it is so short, so packed with interesting dance movements. I wanted to see it right over again.” Robert A. Simon (New Yorker, October 27, 1947):

“It is no small tribute to Mr. Robbins that Interplay gives the impression of just happening rather than of having been staged, and it is danced by eight cheerful, enormously skillful young people who seem to be just kidding around.” Edwin Denby (New York Herald Tribune, November 4, 1945):

“Interplay looks like a brief entertainment, a little athletic fun, now and then cute, but consistently clear, simple, and lively….The characters of Interplay seem to be urban middle-class young people having a good time, who know each other well and like being together but have no particular personal emotions about each other….The intellectual vigor, the clear focus of its overall craftsmanship suggest–as Fancy Free suggested in another way–that Robbins means to be and can be more than a surefire Broadway entertainer, that he can be a serious American ballet choreographer.” Robert Sabin (Dance Observer, December 1945):

“It is a demonstration on the part of Mr. Robbins that he can be ‘abstract’ with the best of them, when he wishes to. Of course there are touches of that comedic spirit which is a hallmark of Mr. Robbins’ best work. But the gist of Interplay is in its design as movement and as a pattern of rhythmic contrasts. Albert Goldberg (Chicago Daily Tribune, December 29, 1945):

“Interplay might have been subtitled ‘The Younger Generation,’ for it enlists ten of the company’s gifted youngsters in a breezy romp that hit last night’s audience squarely between the eyes….Mr. Robbins’ choreography, which tells only such a story as the observer may care to read into it, inherits the exuberance of Fancy Free with a few new wrinkles of its own. The music of Morton Gould invites Americanisms, and in the midst of classic ballet steps, slyly kidded, the dancers suddenly take to handsprings, cartwheels, and a game of leap frog.” |

|

|

|

|

|

November 16, 2023 10:31 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

575 |

| Ballet |

3 |

B3 |

B003 |

Afterthought |

|

Igor Stravinsky |

Suite No. 1 for Small Orchestra, and Suite No. 2 for Small Orchestra |

|

|

By Igor Stravinsky (Suite No. 1 for Small Orchestra, and Suite No. 2 for Small Orchestra). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,946 |

May 2, 1946 |

|

|

New York |

May 2, 1946, New York. |

American Society for Russian Relief (Greater New York Committee) |

|

|

American Society for Russian Relief (Greater New York Committee). |

Nora Kaye, John Kriza |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-The piece was presented by the American-Russian Friendship Society. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

313 |

| Ballet |

4 |

B4 |

B004 |

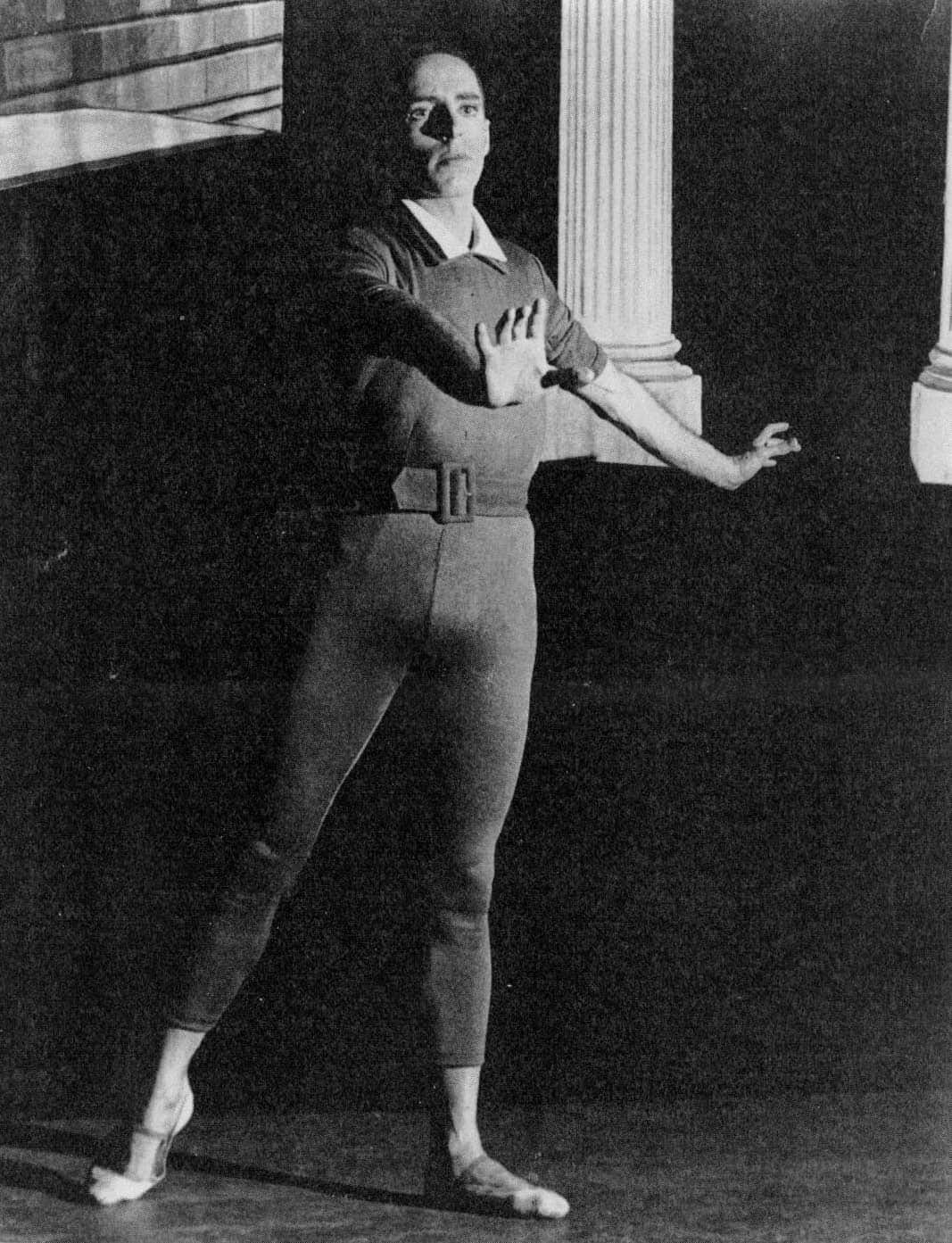

Facsimile |

|

Leonard Bernstein |

Facsimile |

May 29, 1946 |

|

By Leonard Bernstein (Facsimile, 1946). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

Oliver Smith |

Irene Sharaff |

Peter Lawrence |

|

|

|

|

1,946 |

October 24, 1946 |

|

Broadway Theatre |

New York City |

October 24, 1946, Broadway Theatre, New York City. |

Ballet Theatre |

|

In the repertory: 1946-47. |

Ballet Theatre. In the repertory: 1946-47. |

A Woman: Nora Kaye. A Man: Jerome Robbins. Another Man: John Kriza. |

Leonard Bernstein |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“Three insecure people. The scene: A lonely place. The time: The number of minutes the ballet runs, or that many days, weeks, months, or years.” |

-Subtitled “A Choreographic Observation.”

-Inspired by the quotation from Ramon y Cajal, “Small inward treasure does he possess who, to feel alive, needs every hour the tumult of the street, the emotion of the theater, and the small talk of society.” |

|

|

Jerome Robbins (PM, October 24, 1946):

“I’m seriously minded. I don’t want to stick to being the great American ‘yak’ choreographer.” |

John Briggs (New York Post, October 25, 1946):

“It was a troubled, complex affair with all sorts of Freudian overtones….Mr. Robbins calls his work ‘a choreographic observation.’ It was a fairly gloomy observation and a fresh reminder that we are living in perplexing and chaotic times….It was the sort of thing that propels you from the theatre vaguely disturbed and fully expecting to be run down by a streetcar.” Edwin Denby (New York Herald Tribune, October 25, 1946):

“The fact that Jerome Robbins, with four smash comedy hits behind him (two in ballet and two on Broadway), endangered his not yet rooted success as a designer of gay dances by creating the depressing, bitter and not-pap-for-the-audience Facsimile proved that the American choreographer and Ballet Theatre were aware that contrived shadows of past successes could not hope to rival the fresh substance of a new creation. Facsimile was a success, but even if it had been a failure, the validity of its artistic premise could not have been denied.” Irving Kolodin (New York Sun, October 25, 1946):

“Robbins is working here with an idea more subtle and challenging than in his previous works, but he makes his points with clarity–no doubt of that–and a keen sense of physical momentum….It was a lapse of aesthetics, however, to have the woman at her moment of desertion, express in audible sobs what the choreography didn’t.” John Martin (New York Times, October 25, 1946):

“Not an ingratiating piece, by any means, it nevertheless commands respect and raises its creator several notches in the scale of artistic accomplishment….The form of the composition is dramatic rather than choreographic. Though it contains many intricate and appallingly difficult phrases of movement, it has no sustained line of dance, but achieves its continuity by theatrical means. This is in some respects a weakness….It is all a little overwrought, a little superficial; but in spite of such reservations, it is nevertheless an original, admirably sincere and thoroughly to be respected achievement.” Robert Sylvester (New York Daily News, October 25, 1946):

“It’s the new Bernstein-Robbins-Oliver Smith ballet called Facsimile, which Ballet Theatre made the mistake of offering at the Broadway Theater last night….A minute or so before the finale, after the boys have tied her in a tight knot, dumped her on the floor and then fallen on her head, Miss Kaye raises her voice in agonizing appeal…. ‘Stop!’ she cries plaintively. Ballet Theatre should have listened to her at the first rehearsal.” Robert A. Simon (New Yorker, November 2, 1946):

“Dancing is becoming increasingly concerned with psychological matters. Facsimile, according to the program, deals with ‘three insecure people’….The ballet is ingenious and arresting, and it succeeds, because of its compact action, in registering its underlying thought….The three dancers managed their rather difficult roles skillfully, and there was no insecurity or lack of integration in the performance itself.” Edwin Denby (Dance Magazine, December 1946):

“Robbins’s new piece, Facsimile, is an earnest satirical image of a flirtation between an idle woman and two idle men….At a momentary stalemate that postpones the climax, the woman stops the action with a hysterical cry. Politely the men stop. Humiliated but polite, the three leave separately and the stage is empty….Robbins has given his characters a spasmodic grasping drive that indicates they are passionately pretentious….Though timid in that more serious sense, the stage craftsmanship of Facsimile is immensely capable….Facsimile is a big step forward by an honest, exceptionally gifted craftsman.” |

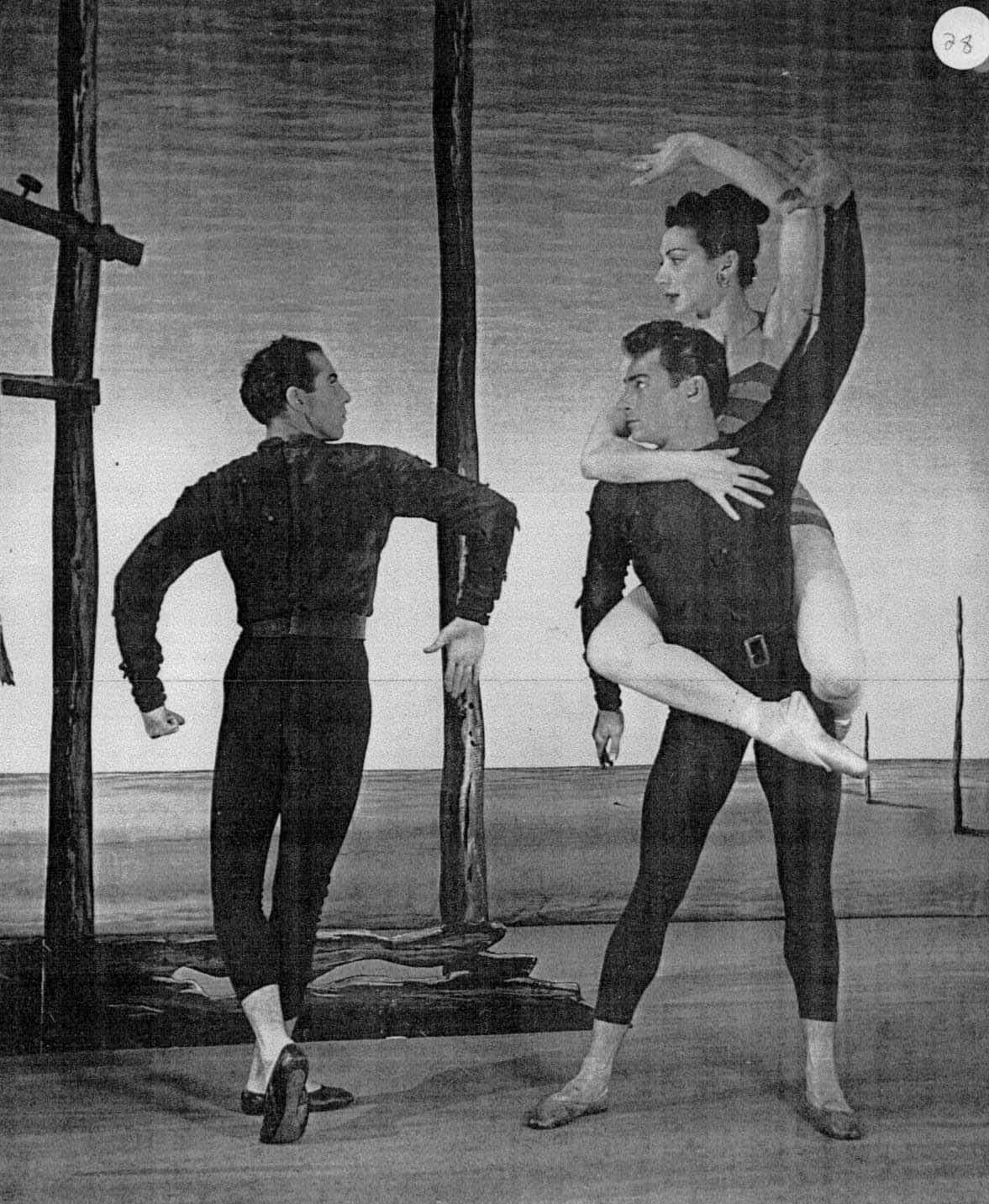

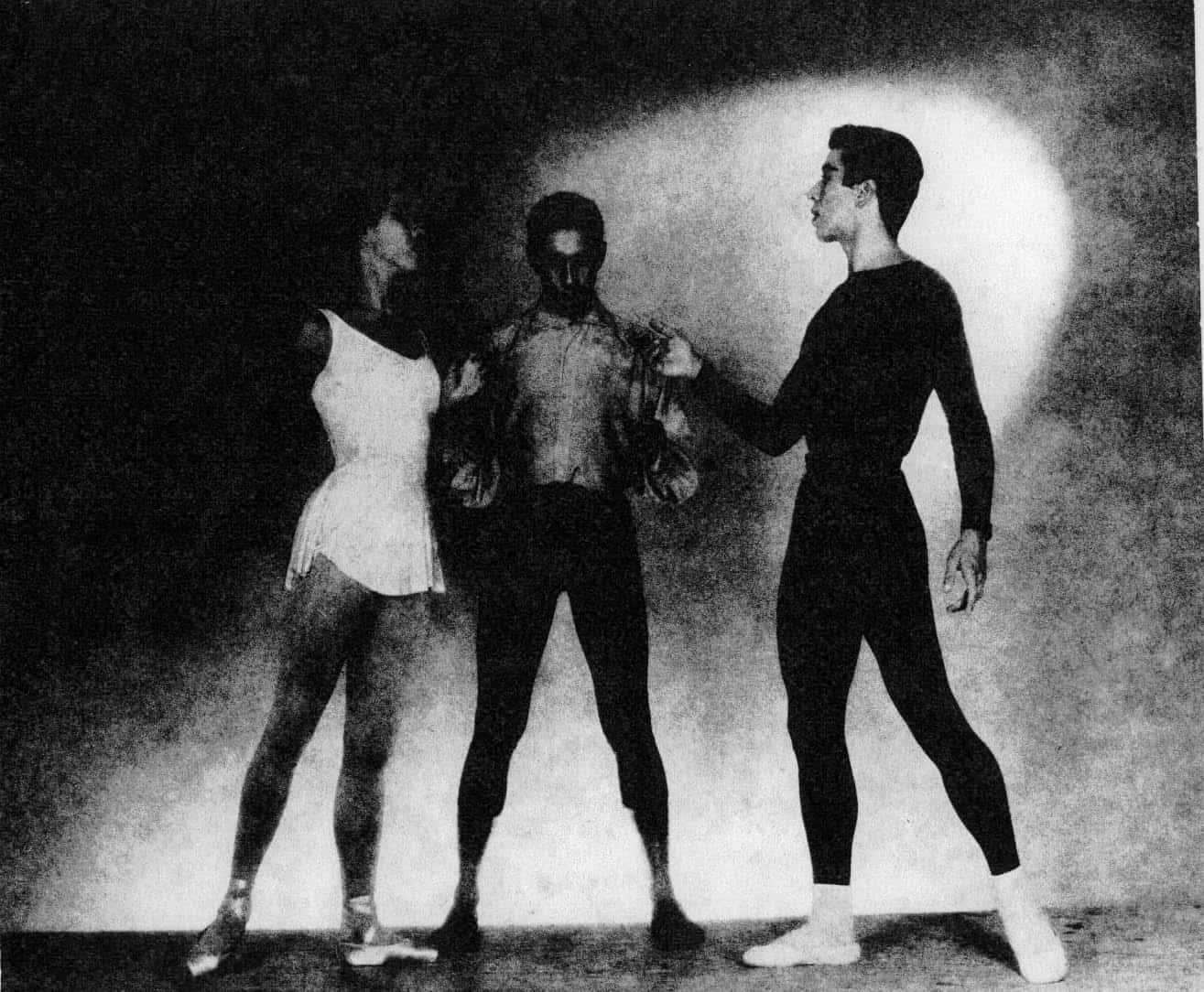

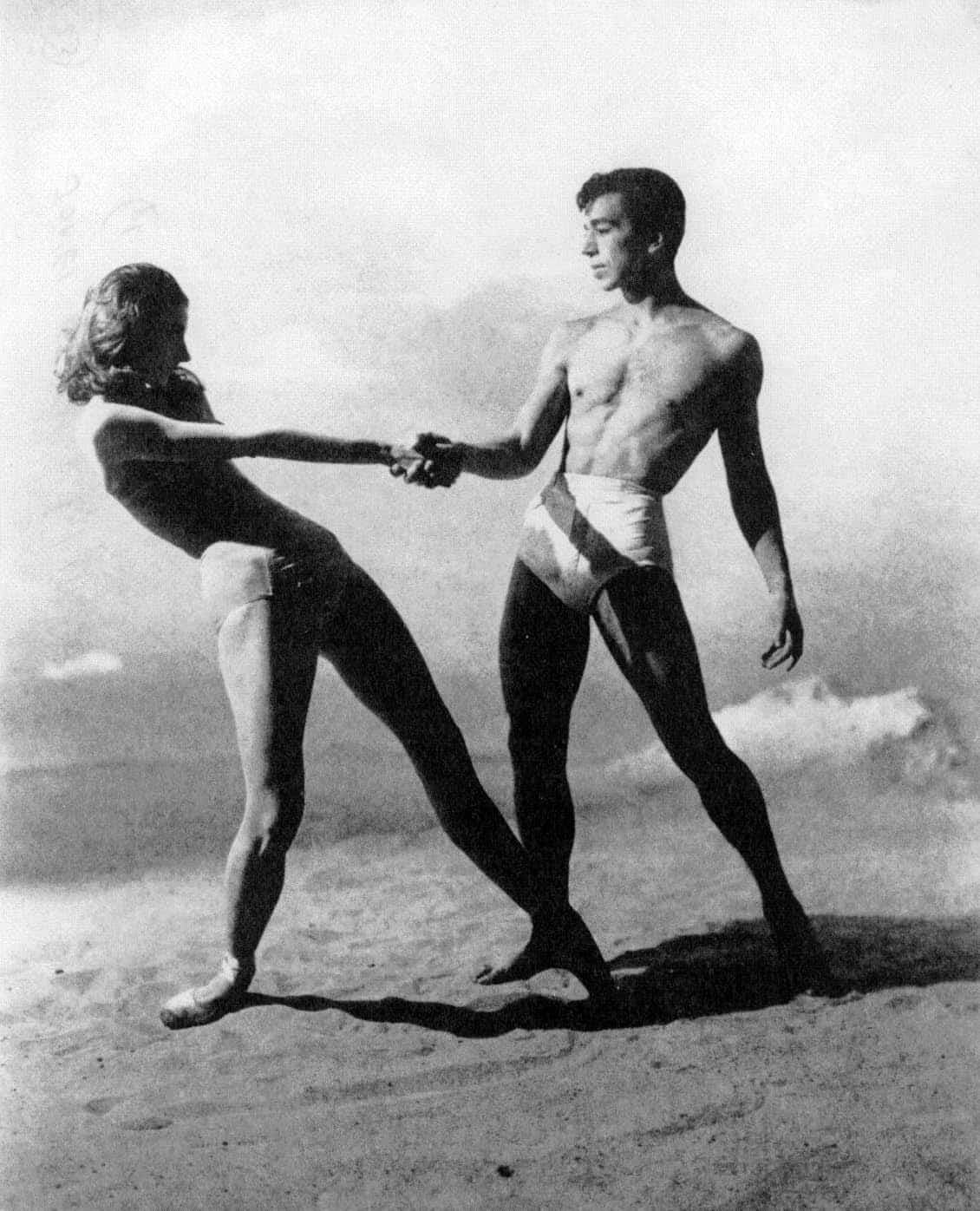

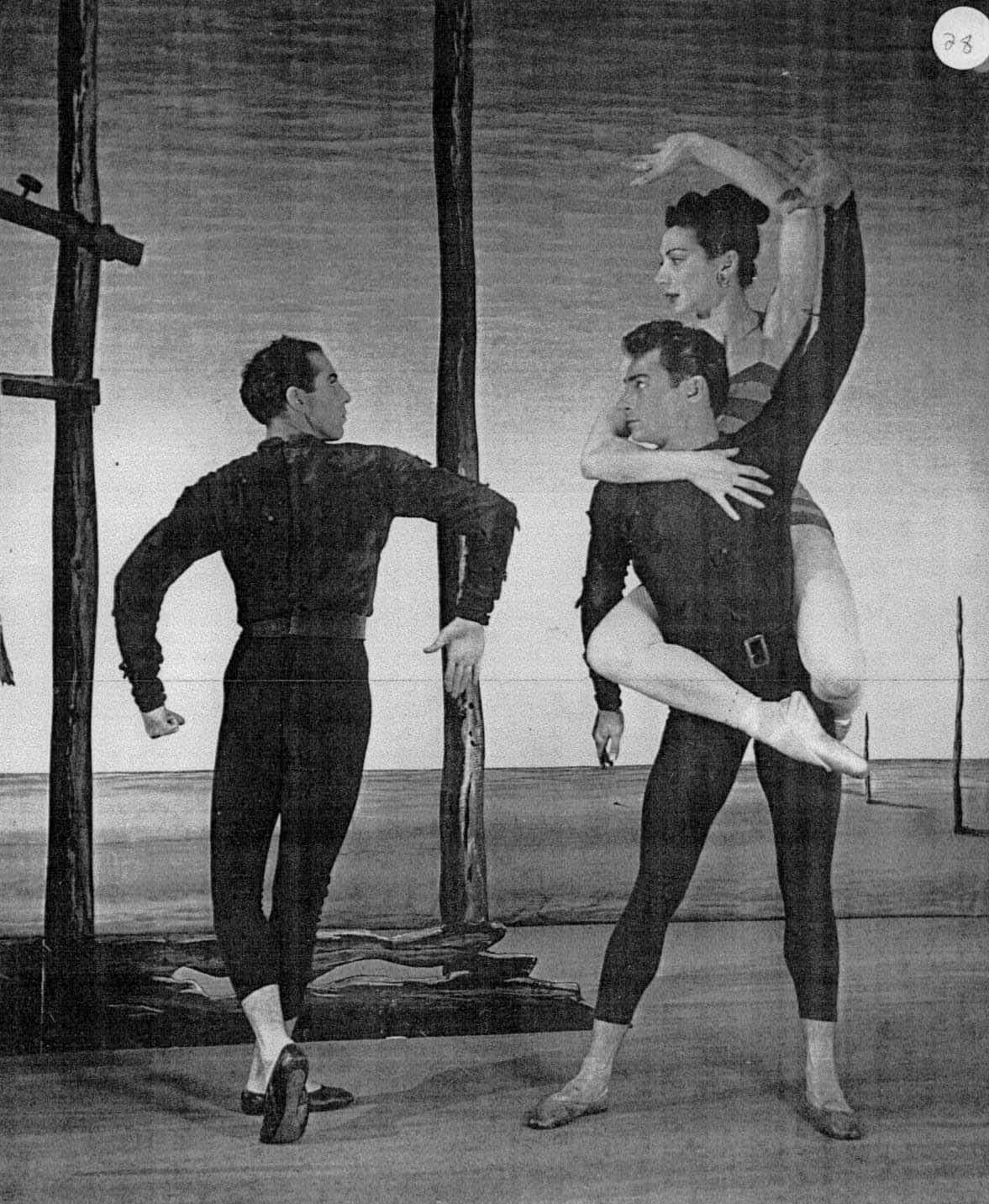

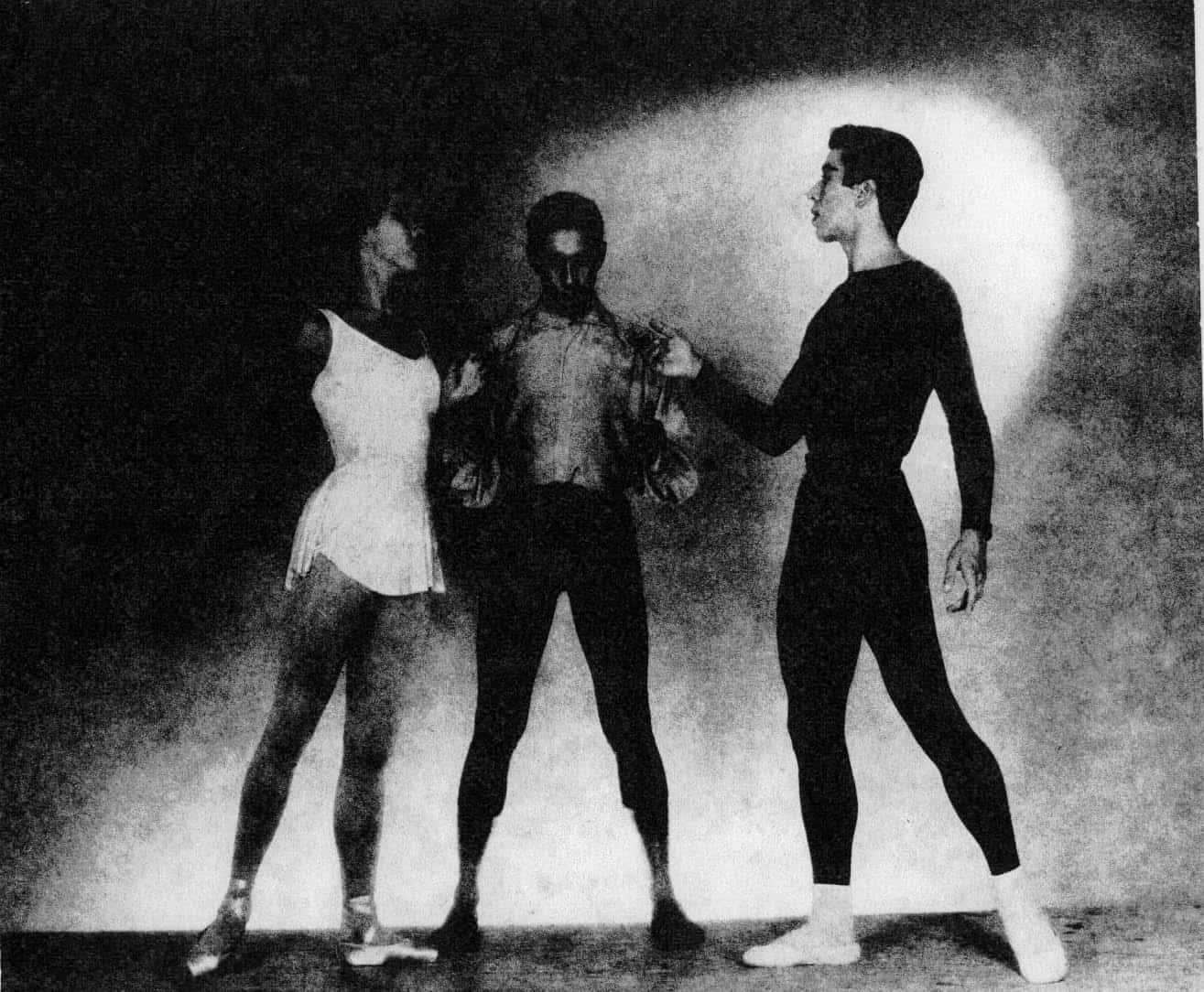

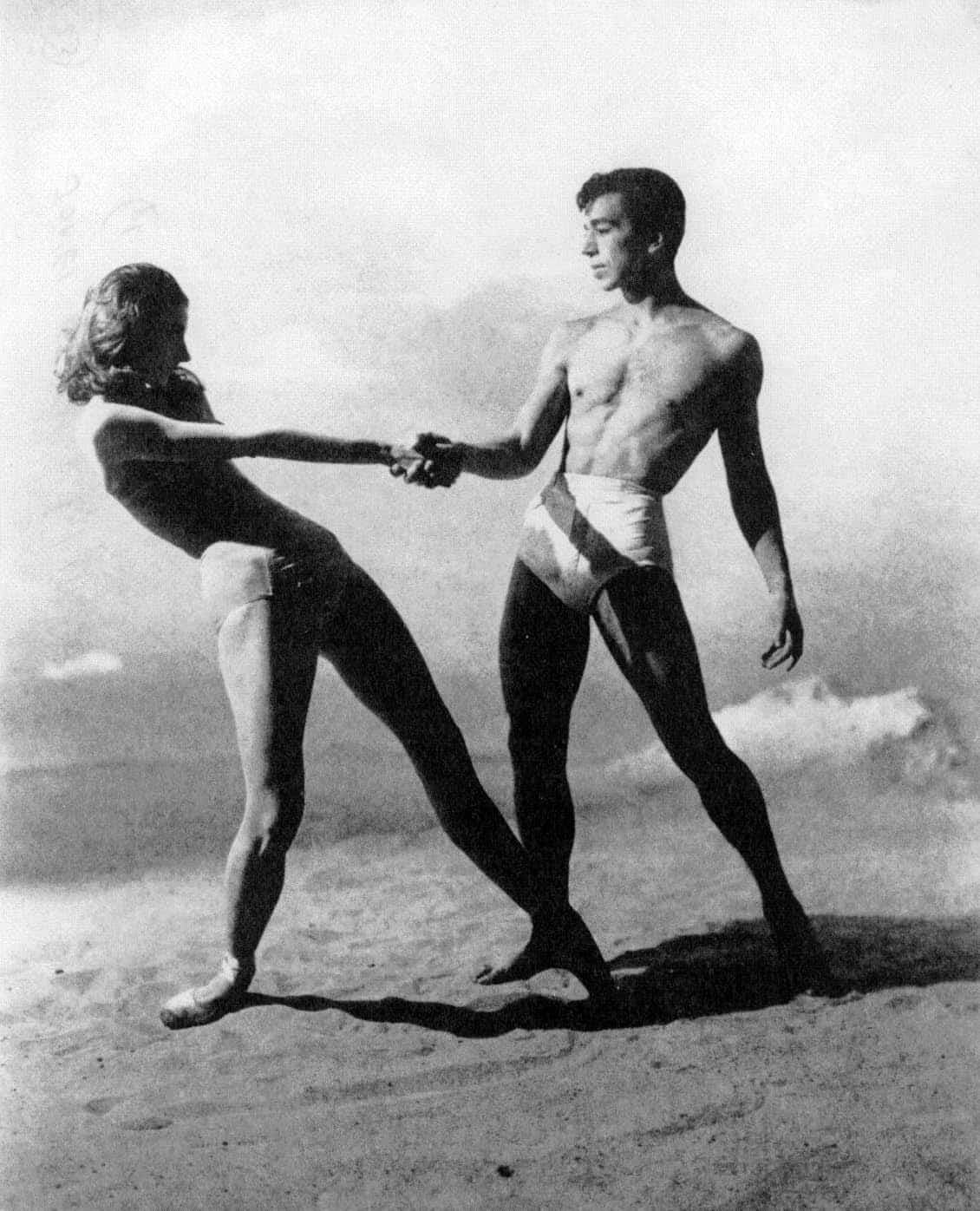

Facsimile: Jerome Robbins, John Kriza, Nora Kaye, 1946. (George Karger)

|

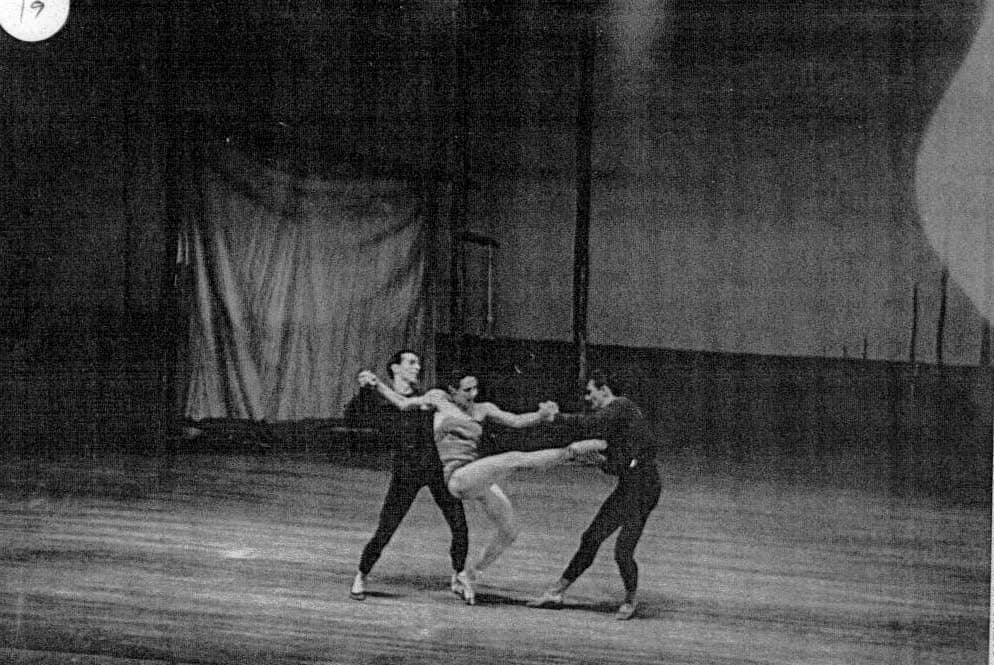

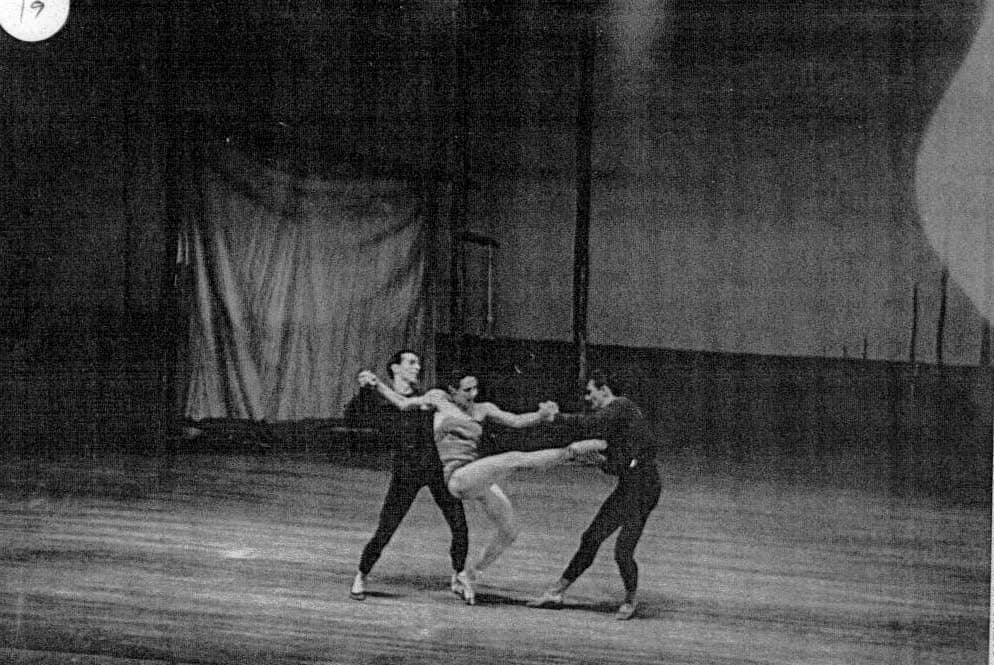

Facsimile: Jerome Robbins, Nora Kaye, John Kriza, 1946. (Fred Fehl)

|

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

314 |

| Ballet |

5 |

B5 |

B005 |

Pas de Trois |

|

Hector Berlioz |

excerpts from The Damnation of Faust |

|

|

By Hector Berlioz (excerpts from The Damnation of Faust). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

|

John Pratt |

|

|

|

|

|

1,947 |

March 26, 1947 |

|

Metropolitan Opera House |

New York City |

March 26, 1947, Metropolitan Opera House, New York City. |

Original Ballet Russe (Col. W. de Basil, Director General) |

|

|

Original Ballet Russe (Col. W. de Basil, Director General). |

Anton Dolin, André Eglevsky, Rosella Hightower. |

Robert Zeller |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-The ballet consists of two sections; a) Minuet and Presto, and b) Waltz. |

|

|

Jerome Robbins (interviewed by Anna Kisselgoff for a New York Times article on May 21, 1990):

“‘Pas de Trois’ had humor in it. It had one humorous section, then one lyrical, lovely section that was sort of a post script. It poked fun at ballet conventions.” |

Irving Kolodin (New York Sun, March 27, 1947):

“The focus throughout was the foibles and fancies of dancers with the three principals on the stage all the time, obscuring each other with malice aforethought, and applause as an afterthought. It is no small matter to sustain a whimsy such as this through twelve minutes or so, but Robbins had a new artifice at hand whenever he needed it. Some of the maneuvers may appeal only to the initiate, but if that is true, there were a remarkable number of them present, and laughing, last night.” Robert Sylvester (New York Daily News, March 27, 1947):

“Jerome Robbins’ Pas de Trois comes about as close to burlesque as it can in a brief eight minute span….There’s every low comedy feature in it from broad mugging to wobbly knees….It’s amusing enough….The main flaw is that, as a piece of comedy, it’s much funnier in the beginning that it is at the end.” John Martin (New York Times, March 28, 1947):

“It is a very amusing and witty little piece, indeed, and it is danced admirably….The moral of his work is that the pas de trios is a mild form of pitched battle no matter how many wreathed smiles are beamed forth as camouflage….It is not only the ‘artistes,’ however, but also the clichés of the ballet that come in for a bit of ribbing, and because Mr. Robbins has a wonderful sense of movement, he has used exaggerated tensions and relaxations to make his points doubly clear. But he is never heavy-handed about it; it all seems perfectly casual and matter-of-fact.” Walter Terry (New York Herald Tribune, March 29, 1947):

“Pas de Trois joshes both the ballet and the stars….It is subtle in its overall pattern, for its sustained humor is predicated upon a hint of what dancers are tempted to do while onstage. A quick glance to see what the others are doing, a surreptitious correction of pose, a passing moment of muscular ennui, a hammy gesture to attract attention, the look of sheer terror when the dancer realizes he has forgotten where to go next, these and other secrets which the dancer normally hides are whispered to the audience during the course of Pas de Trois.” Robert A. Simon (New Yorker, April 5, 1947):

“Pas de Trois is a sure-handed, and sure-footed, satire on virtuoso dancers. Many familiar tricks are overdone or underdone, so that they are reduced to genial absurdity. Nothing is too obvious, though, because Mr. Robbins keeps his parody controlled. There is also an amiable mockery of the moods of dancers at work.” |

|

|

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

315 |

| Ballet |

6 |

B6 |

B006 |

Summer Day |

|

Sergei Prokofiev |

Quartet No. 2, Opus 92 “Music for Children” |

May 31, 1935 |

|

By Sergei Prokofiev (Quartet No. 2, Opus 92 “Music for Children”, 1935). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

|

John Boyt |

|

Ray Lev |

|

|

|

1,947 |

May 12, 1947 |

|

City Center of Music and Drama |

New York City |

May 12, 1947, City Center of Music and Drama, New York City. |

American-Soviet Musical Society |

|

|

American-Soviet Musical Society. |

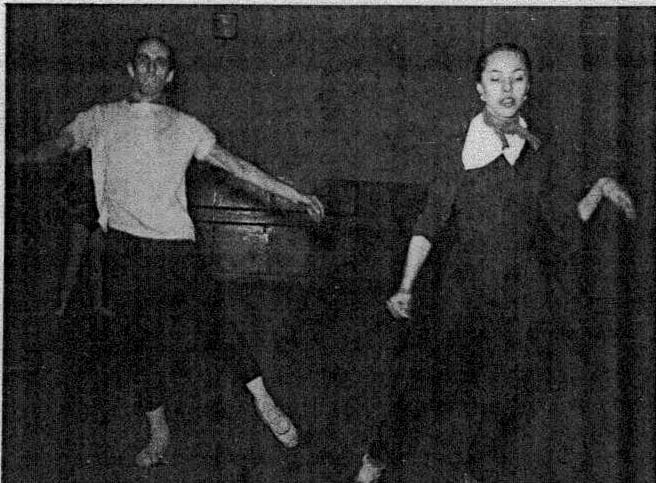

Annabelle Lyon, Jerome Robbins. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“Children while playing make a comment on adult’s behavior. In the same way, the child dancer whose imagination is stimulated by stage props improvises his impressions of a professional.” |

-The ballet is set to the suite for piano “Music for Children” by Prokofiev, several selections of which the composer later made into a symphonic suite titled “Summer Day.”

-The ballet was created for the American-Soviet Musical Society (Serge Koussevitzky, Chairman), on a City Center program titled “Theatre Music of Two Lands” (U.S.A.- U.S.S.R.). Choreographers also presenting works on the program included Valerie Bettis and Charles Weidman. The production was supervised by Marc Blitzstein.

- Note: Jerome Robbins and Ruth Ann Koesun appeared in the 1947 Ballet Theatre staging. |

1947, Ballet Theatre |

|

Jerome Robbins (Boston Herald, December 23, 1947):

“It seems virtually impossible to dance and to design ballets at the same time–one is bound to suffer, with me it is the dancing. For if my head is full of a ballet as a whole, I cannot seem to get the time to practice the essential hour and a half daily that every dancer should in order to do the best work of which he is capable. I am very critical of my own work, and though, as in the case of ‘Summer Day,’ the dance critics were very kind to me, I knew that two days of work were not nearly enough and that the result was not what it should have been.” |

Louis Biancolli (New York World-Telegram, May 13, 1947):

“Number me among those who laughed loudest over the gay spoofing of Jerome Robbins’ ballet lark, Summer Day….The Robbins novelty was deft in its comic build up, yet almost casual on the surface for the secret here was deceptive nonchalance. The horsing around was backed by terrific technique.” Howard Taubman (New York Times, May 13, 1947):

“One can report that the new ballet, witty and playful, won the biggest success of the evening with the audience.” Robert A. Simon (New Yorker, May 24, 1947):

“Mr. Robbins and Annabelle Lyon were highly entertaining in their roles as youngsters working out dance patterns, and Ray Lev, who was at the piano during this number, not only played the music poetically but was so much a part of the arrangement that Summer Day was, in effect, a pas de trios for dancers and pianist.” Robert Bagar (New York Times, December 3, 1947):

“It would not have been entirely amiss if somewhere prominently displayed last night at the City Center there had been a sign reading, ‘Genius at work.’ For Jerome Robbins, the darling of the balletomanes, the Ariel of the dance, was one of the two who appeared in his own choreography for Summer Day.” John Martin (New York Times, December 3, 1947):

“It is a slight work, but an utterly delightful one, brimming with comment that is by no means free from malice, but also touched with tenderness. Using Prokofieff’s piano suite ‘Music for Children,’ Mr. Robbins elects to show how children imitating their elders unwittingly put their fingers on the latter’s weaknesses with devastating accuracy….Mr. Robbins has done his work well; it contains not a single waste movement, it has style and form and charm as well as satire, and in spite of its fragility, bears more witness to the great talent of its creator.” Miles Kastendieck (New York Journal-American, December 3, 1947):

“There isn’t much to it, but what there is has a kind of perfection peculiarly Robbins. The audience loved it.” Walter Terry (New York Herald Tribune, December 3, 1947):

“During this romp one may detect pointed comments on such prevalent balleticisms as the ballerina’s cloying concern for the beauty of her own line, self-conscious excursions into the realm of pseudo-folk dance, adagio swoons and other activities familiar to the balletomane….To the male role, Mr. Robbins brought his familiar and welcome sense of humor and his considerable skill as a dancer. His dance wit, which finds its trademark in what might best be called the ‘Robbins walk’–purposeful in stride, outwardly innocent but boding mischief at trail’s end–is of the relaxed variety, logical and unforced.” Robert Sylvester (New York Daily News, December 4, 1947):

“Jerome Robbins’ new Summer Day is a highly amusing piece of slapstick and satire. Its slapstick is almost as hokey as Fanny Brice’s old ‘Dying Swan’ and its satire is enough to make Anton Dolin holler for his lawyers….While Robbins has brought something of value to the Broadway theatre from ballet in recent years, he is now equipped to bring back something in return from his studies in the rowdy musical comedy field.” Frances Herridge (PM, December 7, 1947):

“Summer Day was the sunny spot in last May’s concert of the American-Soviet Music Society, for whom Robbins created it. Polished up a bit and added to the Ballet Theatre’s repertoire, it was the hit of last Tuesday’s program….It remains to be seen how time will treat Summer Day. It hasn’t the substantial workmanship of Robbins’ Facsimile, Interplay or Fancy Free. Spun of ingenious whimsy and easy wit like his recent Pas de Trois, it may well not weather repeated showings. Its spontaneity can easily become forced; its charm, along with its balletic jokes, runs the risk of being over-cute.” Walter Terry (New York Times, December 7, 1947):

“Summer Day is a wonderful excursion into the area of adolescent playfulness….Mr. Robbins has woven these dance comments together with seemingly natural but carefully choreographed movements, such as a walk, a yawn, a passing gesture, a glance, and the result is a ballet, or a theatre piece, which presents a refreshing brand of satire. In this case the satire is born of innocence, and when ridicule, devastating comment and frightening honesty emanate from innocence they appear to be inarguable and therefore more potent. Through his child characters in Summer Day Mr. Robbins says much, and says it winningly.” Douglas Watt (New Yorker, December 13, 1947):

“An amusing pas de deux that shows what happens when a couple of children get their hands on the stage props of professional dancers. The result is a boisterous parody of all sorts of ballet techniques.” Claudia Cassidy (Chicago Daily Tribune, January 6, 1948):

“Summer Day goes right on endearing ballet to those who cherish it doubly because when it looks in a mirror it sometimes sees a whimsical reflection….Onstage come two child dancers, Ruth Ann Koesun and John Kriza, who enliven a practice period by dressing up and emulating their not always impeccable elders….That’s all there is to it except that these are charming children with the relaxed, off-guard quality Mr. Robbins captured in Interplay….Here he suggests it in childlike variation culminating in the budding big brother protectiveness with which the boy scoops up the girl and carries her home.” |

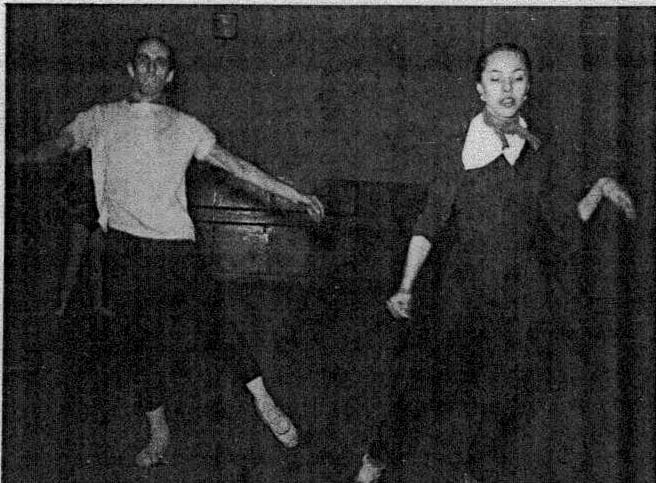

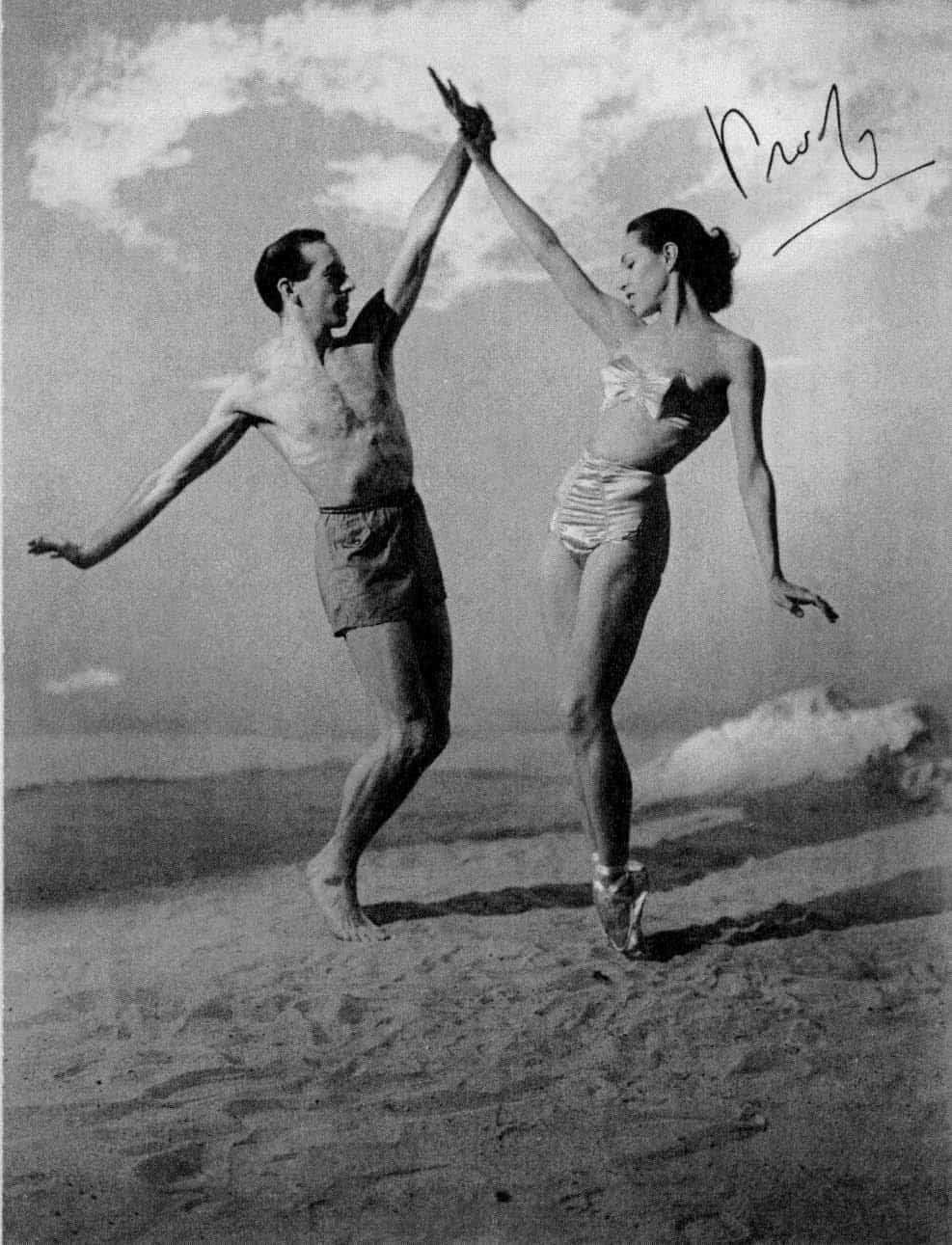

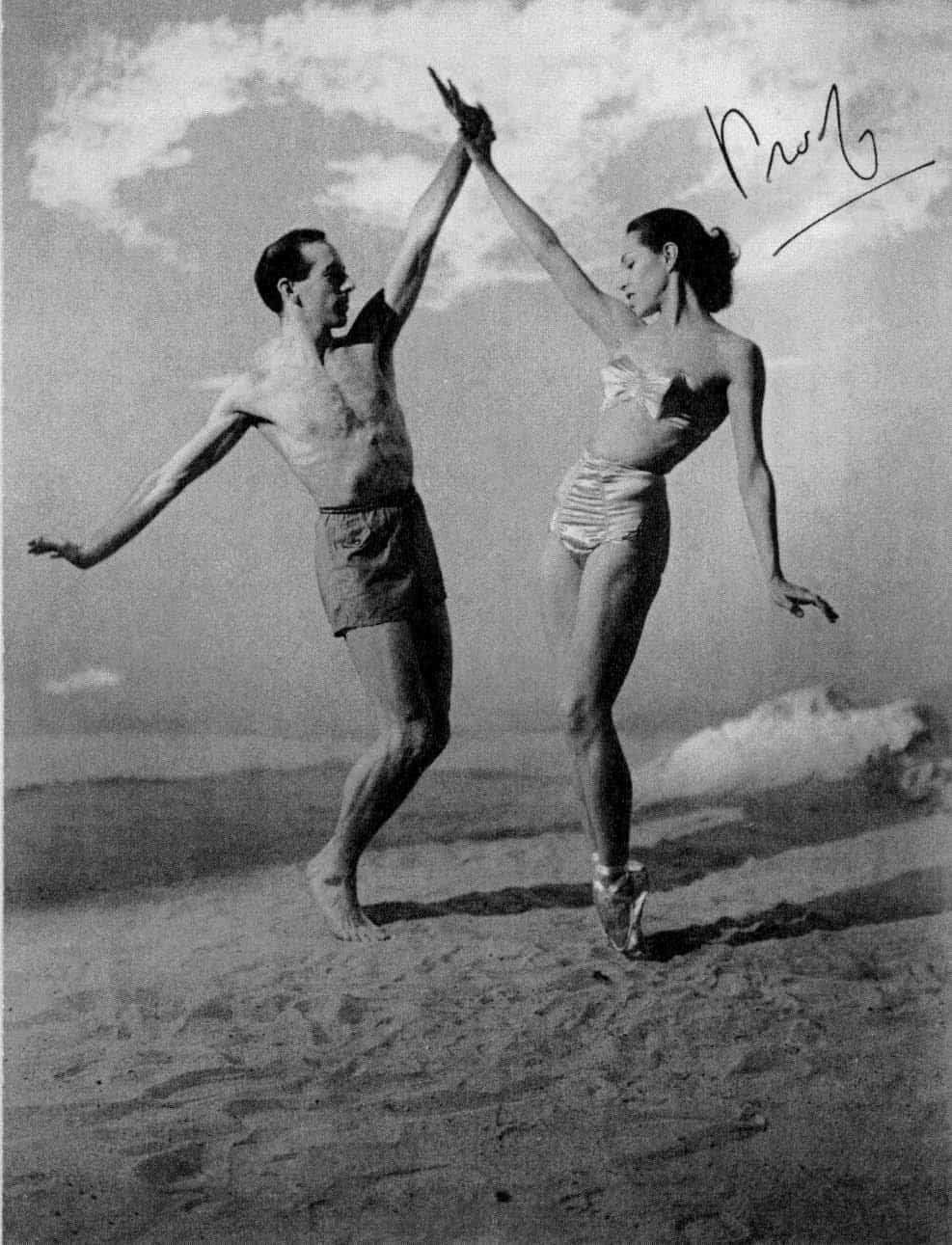

Summer Day: Annabelle Lyon, Jerome Robbins, 1947. (Graphic House)

|

Summer Day: Jerome Robbins, Annabelle Lyon, Ray Lev, 1947. (Graphic House)

|

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

316 |

| Ballet |

7 |

B7 |

B007 |

The Guests |

|

Marc Blitzstein |

The Guests |

January 1, 1949 |

|

By Marc Blitzstein (The Guests, 1949). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

|

|

Jean Rosenthal |

|

|

|

|

1,949 |

January 20, 1949 |

|

City Center of Music and Drama |

New York City |

January 20, 1949, City Center of Music and Drama, New York City. |

New York City Ballet |

|

In the repertory: 1949-50. |

New York City Ballet. In the repertory: 1949-50. |

Maria Tallchief, Nicholas Magallanes. The Host: Francisco Moncion. First Group: Dorothy Dushock, Herbert Bliss, Kaja Sundsten, Dick Beard, Arlouine Case, Brooks Jackson, Pat McBride, Edward Dragon, Una Kai, Jack Kauflin. Second Group: Rita Carlin, Roy Tobias, Margaret Walker, Walter Georgov, Barbara Milberg, Luis Shaw. |

Leon Barzin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“A ballet in one scene concerning the patterns of adjustment and conflict between two groups, one larger than the other.” |

-This was the first ballet Robbins created for New York City Ballet. |

|

|

Jerome Robbins (New York Times, June 3, 1990):

“The ballet had a commissioned score. Marc (Blitzstein) wanted to make it very concrete and to have it take place in a department store and have a party between the help. I tried to pull it out of that into something more abstract.” |

Louis Biancolli (New York World-Telegram, January 21, 1949):

“With a forceful score by Marc Blitzstein and choreography by Jerome Robbins, the novelty worked up tense momentum on two levels. On one it was a slick study in shifting classical groups and patterns, based on the Robbins principle of interlocked motion….On the social plane, The Guests was a satiric blast at all forms of class exclusion. The use of masks–to conceal the identity of the unwanted–added a final note of hypocrisy.” Harriett Johnson (New York Post, January 21, 1949):

“Though no hint was given in the program regarding its significance, it was obvious that the central idea of the work centered around two different groups of society, one of which was the object of discrimination….Using conventional ballet technique as its means of expression, the work has many poignant moments, but the choreography is not consistently fresh or original.” John Martin (New York Times, January 21, 1949):

“It is subtitled a ‘classic ballet’ but it also has a definite social theme, that of intolerance. The guests of the title consist in part of those who wear a glittering cast-mark on their foreheads and are accordingly accepted by the host, and those who have unadorned brows and are not accepted. The conflict is joined in a very neatly contrived Romeo and Juliet romance….It is quite obvious and somewhat overstated. For the most part Mr. Robbins seems more concerned with the topic than with the choreography….There are a few bits of startlingly banal pantomime….On the whole, a disappointing work.” Robert Sylvester (New York Daily News, January 21, 1949):

“The highlight of The Guests is the brief but effective solo by Maria Tallchief, to a haunting and lovely Blitzstein strain, and a thoroughly superb pas de deux by Miss Tallchief and Nicholas Magallanes. If The Guests would only build from these choreographic and musical peaks, it would be brilliant. Instead the new ballet trails off both musically and visually.” Walter Terry (New York Herald Tribune, January 21, 1949):

“If The Guests, in its current form is not a great ballet, it is, nevertheless, an absorbing one which adds stature to its young choreographer and which augurs new directions for classic dance….By inflection through movement attack and by shrewd juxtapositions of steps and ensemble actions, Mr. Robbins has invested his classic pas with dramatic purpose. Some gesture, some touches of purely expression movement have, of course, been used to transmit the emotional colorings of the work….There is no story to The Guests. It is, I would say, incident without circumstance; it implies situation without explaining condition.” Frances Herridge (New York Star, January 23, 1949):

“Using two opposing groups of dancers, Robbins has worked out a series of movement interactions in the modern ballet vocabulary of Balanchine….The two groups and the lone figure who introduces them are symbolic. What they represent becomes a fascinating puzzle….The two groups can represent any opposing cultures, religions, or peoples. The intolerant host may symbolize social authority, the mores, inflexible public opinion, or perhaps arbitrary dictatorship. It may be a picture of Nazism, of the caste system, or social censure of opposing marriages: Negro with White, Easterner with Westerner, Jew with Gentile. See it yourself and work it out.” B.H. Haggin (Nation, February 19, 1949):

“Jerome Robbins, who has produced brilliant comedy seems to want to show he can deal with serious matters too….It includes a pas de deux with some lovely movements; but the invention for the large groups is uninteresting.” |

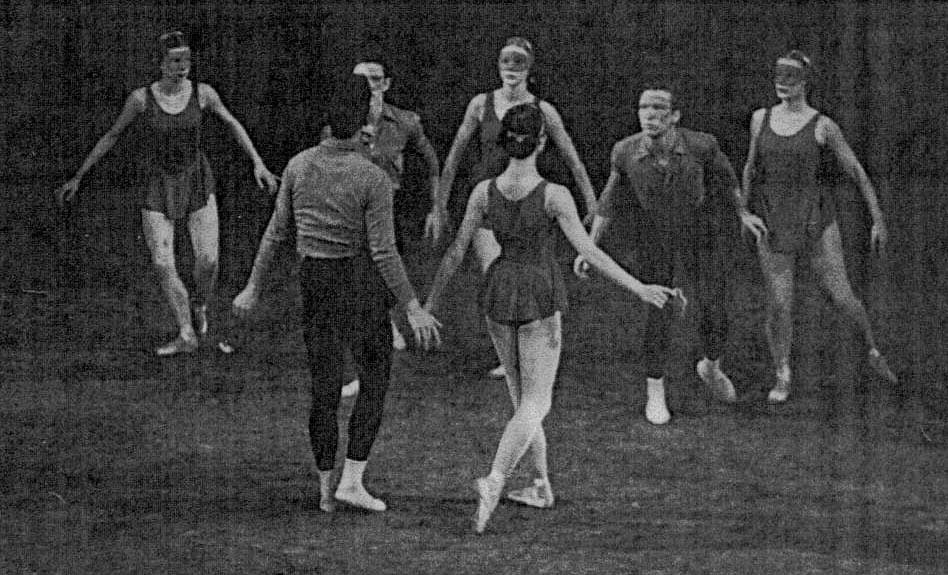

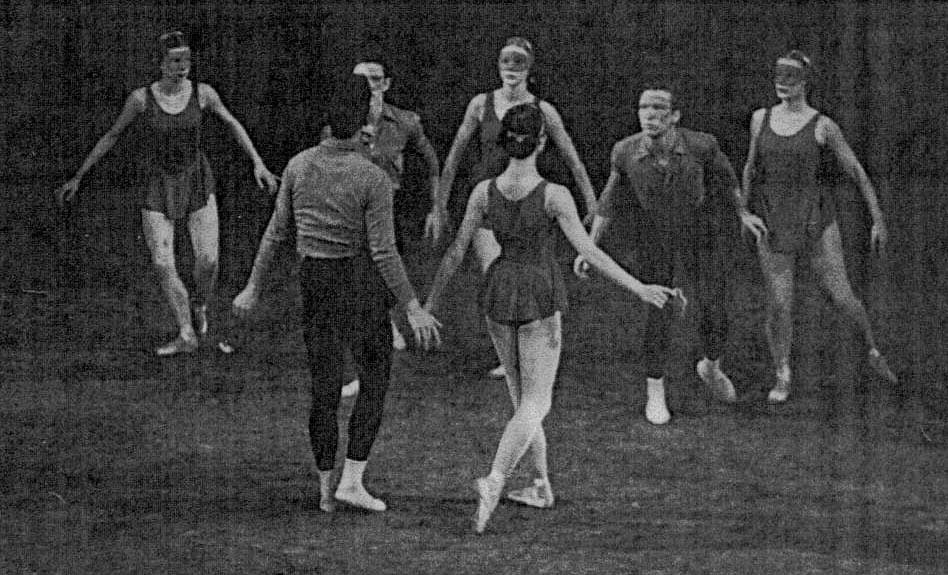

The Guests: Maria Tallchief, Jerome Robbins, Nicholas Magallanes, 1949. (George Platt Lynes)

|

The Guests: Nicholas Magallanes, Maria Tallchief (in the foreground), 1949. (Fred Fehl)

|

The Guests curtain call: Nicholas Magallanes, Maria Tallchief, Jerome Robbins, and Marc Blitzstein, 1949. (Fred Fehl)

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

317 |

| Ballet |

8 |

B8 |

B008 |

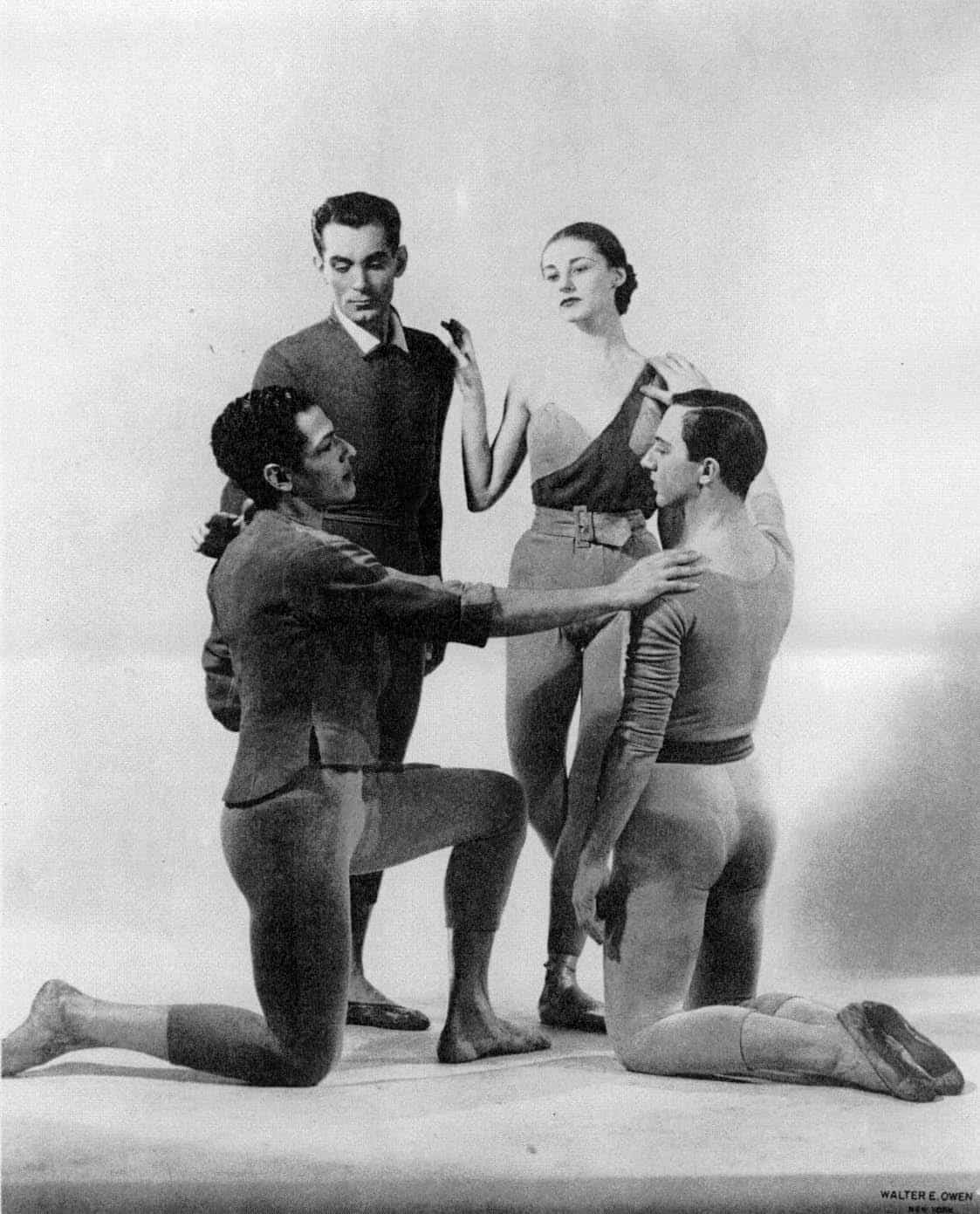

Age of Anxiety |

|

Leonard Bernstein |

Symphony No. 2 for Piano and Orchestra [“The Age of Anxiety”] |

January 1, 1949 |

|

By Leonard Bernstein (Symphony No. 2 for Piano and Orchestra [“The Age of Anxiety”], 1949). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

Oliver Smith |

Irene Sharaff |

Jean Rosenthal |

Nicholas Kopeikine |

|

|

|

1,950 |

February 26, 1950 |

|

City Center of Music and Drama |

New York City |

February 26, 1950, City Center of Music and Drama, New York City. |

New York City Ballet |

|

In the repertory: 1950-57. |

New York City Ballet. In the repertory: 1950-57. |

The Prologue (Four strangers meet and become acquainted): Francisco Moncion, Tanaquil Le Clercq, Todd Bolender, Jerome Robbins. The Seven Ages (They discuss the life of man from birth to death in a set of seven variations): Yvonne Mounsey, Pat McBride, Beatrice Tompkins, Arluoine Case, Robert Barnett, Dorothy Dushock, Val Buttignol, Edwina Fontaine, Walter Georgov, Jillana, Brooks Jackson, Una Kai, Roy Tobias. The Seven Stages (They embark on a dream journey to find happiness): Melissa Hayden, Herbert Bliss, Dick Beard, Shaun O’Brien, Audrey Allen, Barbara Bocher, Joan Bonomo, Doris Breckenridge, Ninette d’Amboise, Edwina Fontaine, Peggy Karlson, Helen Komaova, Barbara Milberg, Francesca Mosarra, Janice Nagley, Moira Paul, Ruth Sobotka, Barbara Walczak, Margaret Walker, Tomi Wortham. The Dirge (They mourn for the figure of the All-Powerful Father who would have protected them from the vagaries of man and nature): Edward Bigelow, Arlouine Case, Jillana, Una Kai, Pat McBride, Yvonne Mounsey, Robert Barnett, Val Buttignol, Jacques d’Amboise, Walter Georgov, Brooks Jackson. The Masque (They attempt to become or to appear carefree): Full Cast. The Epilogue. |

Leon Barzin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“This ballet was inspired by Leonard Bernstein’s Symphony No. 2 and the W. H. Auden poem on which it is based. The ballet follows the sectional development of the poem and music and concerns the attempts of people to rid themselves of anxiety.” |

-Based on the poem “The Age of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue” by W. H. Auden (1946) |

|

|

Jerome Robbins:

“It is a ritual in which four people exercise their illusions in their search for security. It is an attempt to see what life is about.” |

Frances Herridge (New York Post, February 27, 1950):

“In this most ambitious work of his career, Jerome Robbins has done an admirable job of converting into dance terms Auden’s complex poem about four characters in search of life’s meaning.” Miles Kastendieck (New York Journal-American, February 27, 1950):

“Like the symphony, the ballet falls into six parts during which four lonely characters seek answers to their questions about life….What gives the work power is Robbins’ gift for mood. Section by section its quality varies.” John Martin (New York Times, February 27, 1950):

“This is the kind of production that justifies the City Ballet’s existence….Robbins’ intuition is uncannily penetrating, his emotional integrity is unassailable and his choreographic idiom is lean and strong and dramatically functional. He has a fine theatre sense, can evoke an atmosphere by means that are somehow never definable, and knows how to get from his dancers qualities that perhaps even they themselves are not aware that they possess.” Walter Terry (New York Herald Tribune, February 27, 1950):

“Through his choreography Mr. Robbins outlines the life and thought patterns of his four protagonists, three men and a girl….But Age of Anxiety is more than a successful etude. It is an enormously compelling work of art. I cannot offer a synopsis, for it is not a story; it is an experience. The four who guide its course are the frightened souls of an anguished era and we share in their experiences, both real and imagined….It is an emotional experience communicate through dance, through Mr. Robbins’s perceptive and eloquent dance.” Douglas Watt (New York Daily News, February 27, 1950):

“The New York City Ballet Company’s most ambitious new production, The Age of Anxiety, proved to be a tiresomely sentimental piece of claptrap….The only time the anxious thing really got going was when Robbins, who himself danced one of the four main characters, and poorly, had his dancers cut loose with a musical comedy pattern. He dropped this quickly, however, lest anybody get to enjoy it too much.” Doris Hering (Compass, February 28, 1950):

“Jerome Robbins’ Age of Anxiety is like the proverbial flower growing through a crack in the pavement. It has about it the restlessness and emotional economy of human relationships in a modern city, and yet throughout there keeps rising a persistent and wholly convincing core of faith and simple goodness….Although plenty of knotty psychological and religious ideas were implied in the poem, the ballet, and even the score, Mr. Robbins never lost sight of the fact that he was dealing, above all, with human beings. As a result, his choreography, though highly imaginative, retained its human dimension.” Bron. (Variety, March 1, 1950):

“Age of Anxiety is Robbins’ choreography to the new symphony of Leonard Bernstein, the libretto dealing with the current day unrest and man’s problem to find inner peace and security. Piece is serious in theme, unlike the onetime Robbins/Bernstein comedy ballet hit, Fancy Free. Work isn’t completely successful, due to too much weltschmerz. Quartet of dancers who play the protagonists establish their point early that this is the age of anxiety and unrest, and reiteration of this point through repetition of poses and gestures makes for monotony.” Louis Biancolli (New York World-Telegram, March 10, 1950):

“The ballet is good fun from beginning to end….Jerome Robbins and George Balanchine have done another superb job of mass choreography here. The group movements swirl all over the stage, and somehow the tang of the outdoors gets into the motion….On all points the Jones Beach ballet is worth a view as the next best thing to a day in the sun.” Robert Sylvester (New York Daily News, March 10, 1950):

“The choreography found George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins expertly blending their dissimilar styles and all the dancers apparently having fun at work….It’s a ballet in four parts which touches upon everything from mosquitoes to lifeguards and, of course, a beach full of pretty girls.” Emory Lewis (Cue, March 11, 1950):

“Jerome Robbins has chosen to translate W.H. Auden’s obscure poems, ‘Age of Anxiety,’ into ballet terms, and to indicate that, in our troubled world, faith is the answer….Because the theme is itself controversial and unacceptable to many mundane minds, the ballet has a strike against it at the onset….Jerome Robbins has outdone himself in imaginative choreography. Yet somehow the whole thing adds up to disappointment.” Doris Hering (Compass, March 12, 1950):

“The ballet itself was a big, lively mixture of Jantzen bathing suits, satin toe shoes, realism and classic movement….But it kept checking itself and slipping back into ballet clichés, as though it were rather afraid to let its hair down all the way….In other words, the material is there. It’s waiting for the choreographers really to develop it. But in the meantime, it was a pleasure to see this large group of handsome, healthy looking young people freed of the tyranny of tights and tutus.” B.H. Haggin (Nation, March 18, 1950):

“It is another example of what happens when Robbins’s sharp eye and satiric sense concern themselves with American lowbrow dancing; and it makes one wish that if he feels that as a serious artist he must deal with serious subjects he would deal with them in comedy, of which he is so brilliant a master.” Ann Barzel (Chicago Sun, March 26, 1950):

“Age of Anxiety is a profound and complex work….The overall intention is clear, the moods are set immediately, the very patterns of the dances project feeling. There are passages when the stage is full of dancers whose individual steps and group designs are in themselves as stunning as abstract dance aside from any communicative function….Robbins himself is the best of the four anxious characters. He never walks into a pose. There is always an evident inner compulsion for each movement.” Anatole Chujoy (Dance News, April 1950):

“In no sense a choreographic retelling of Auden’s Pulitzer Prize-winning poem, Age of Anxiety is a great original ballet and, probably, the beginning of a new period in the creative life of Robbins….Age of Anxiety is a ballet that cannot be described in simple terms, nor can its powerful impact be fully realized from one seeing. Here is a ballet to be seen again and again, a ballet whose profound theme has a way of obscuring at the beginning the wonderful dancing Robbins has devised to carry the theme.” Doris Hering (Dance Magazine, April 1950):

“Mr. Robbins has penetrated into that fluid realm where only movement speaks–and what original movement it is! He has found us a rich, intuitive picture of today’s world with its gnawing quest for identity….The ballet concerns four strangers who meet, discuss the life of man from birth to death, embark upon a dream journey, mourn for a universal father-symbol, try to shake off their mutual despair with a gay dance, and finally discover a source of faith and strength each within himself.” Nik Krevitsky (Dance Observer, April 1950):

“This work, a definite development or coming of age as a serious artist, on the part of Jerome Robbins, is extremely evocative, beautifully structured, and filled with invention and variety which make it a truly great dance piece. There is a universality in its treatment of the theme, and in the objective portrayal of the four characters, that maintains the strength of the work throughout….Age of Anxiety, built like most Robbins compositions, uses the element of contrasting quality to maintain interest and lend variety to the entire proceedings.” |

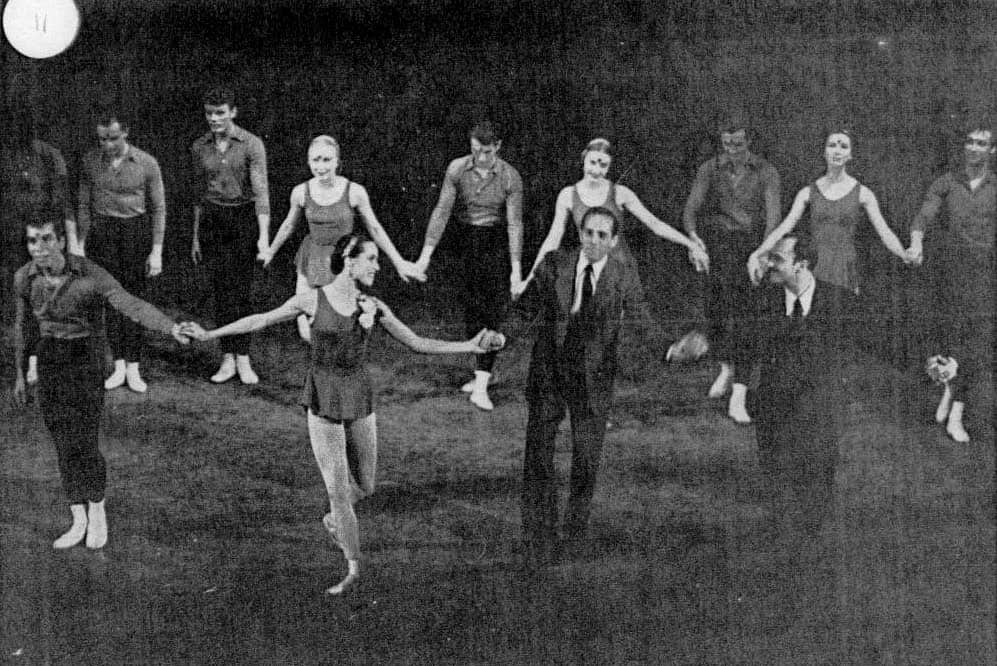

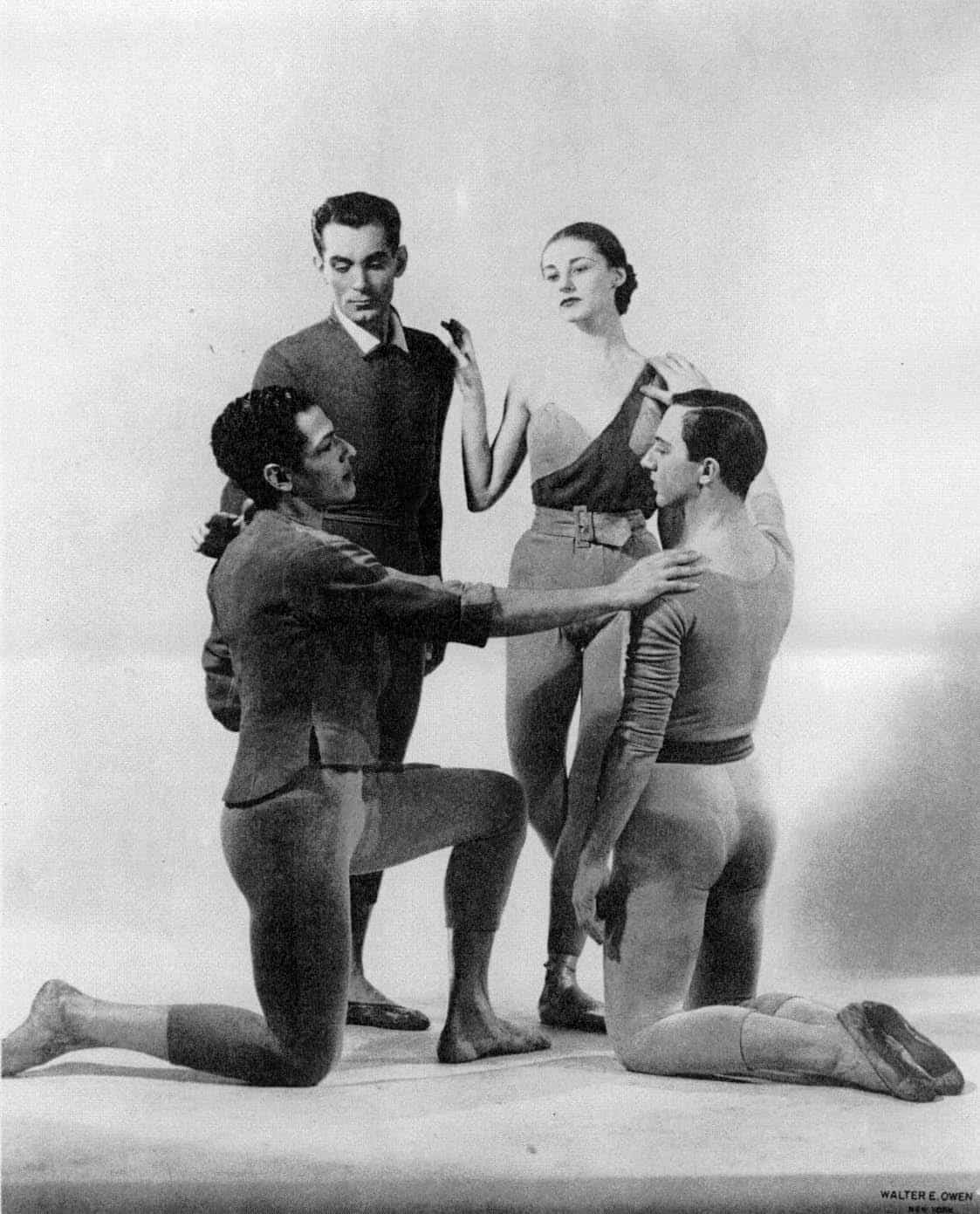

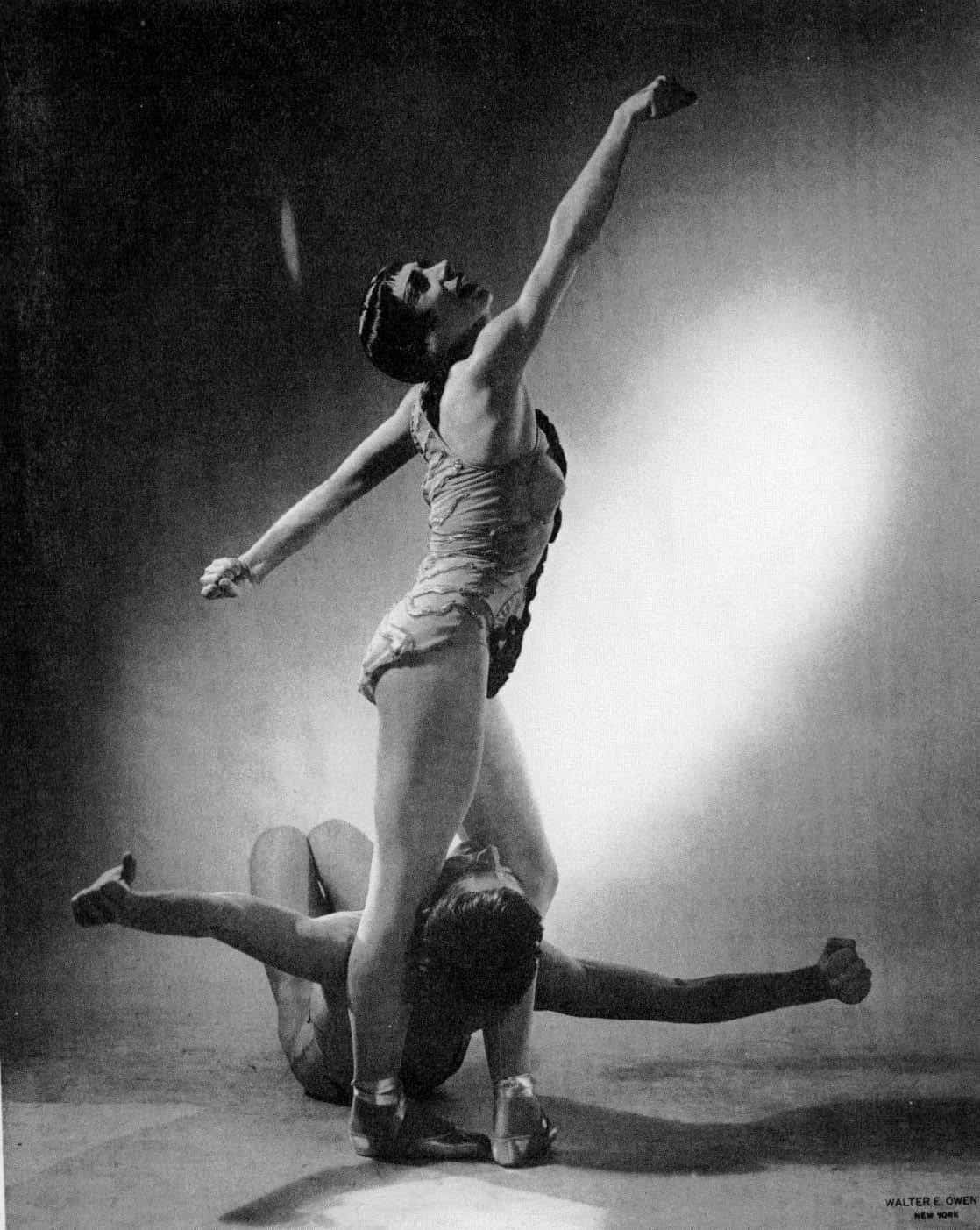

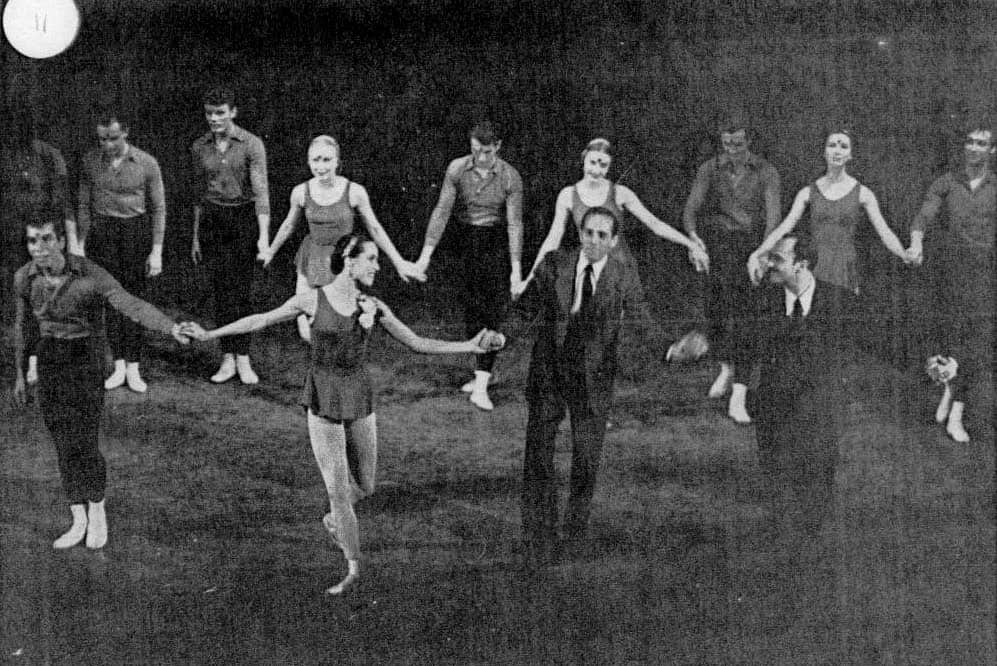

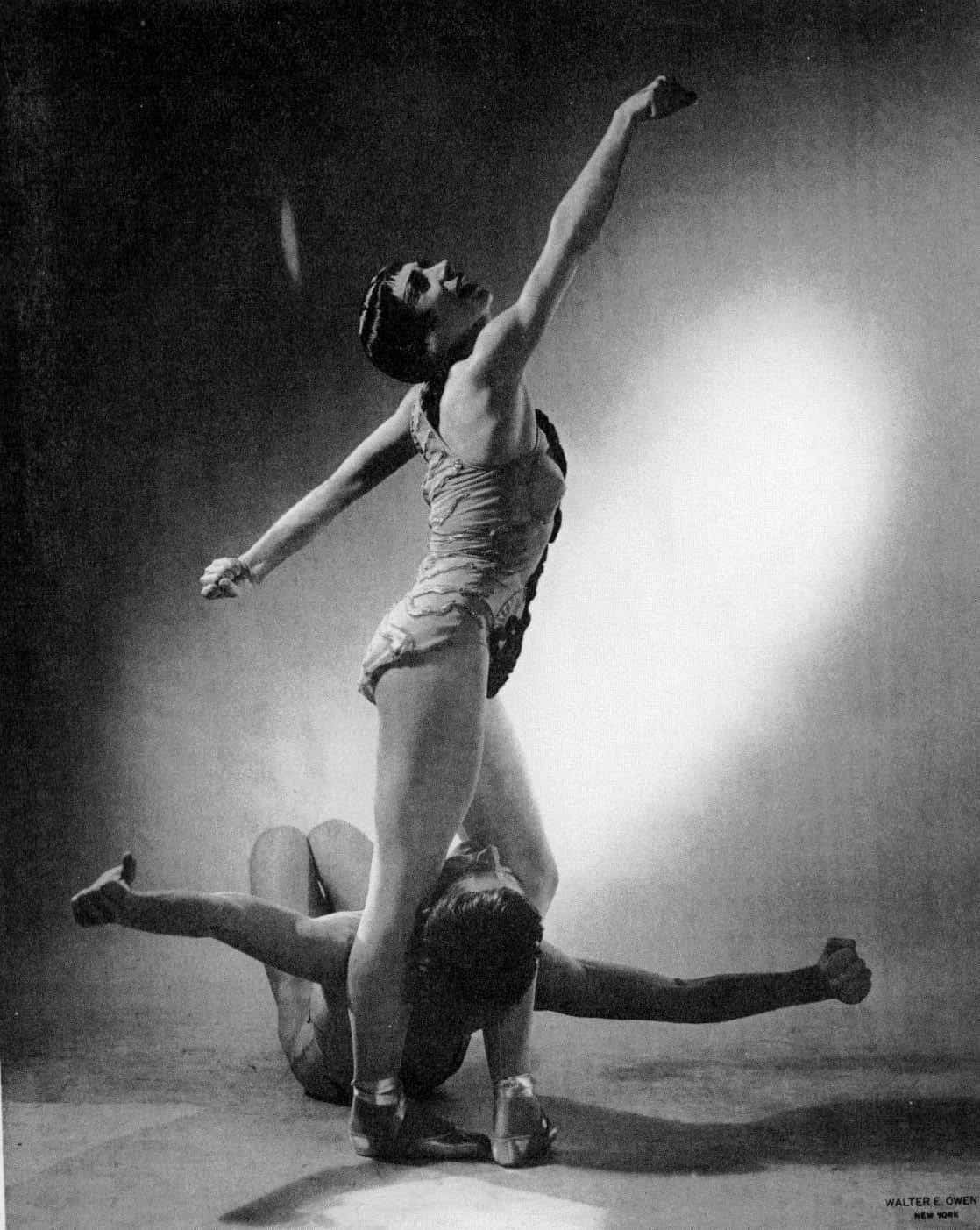

Age of Anxiety: Robert Barnett (on left) and Jerome Robbins rehearsing dancers, 1950. (Walter E. Owen)

|

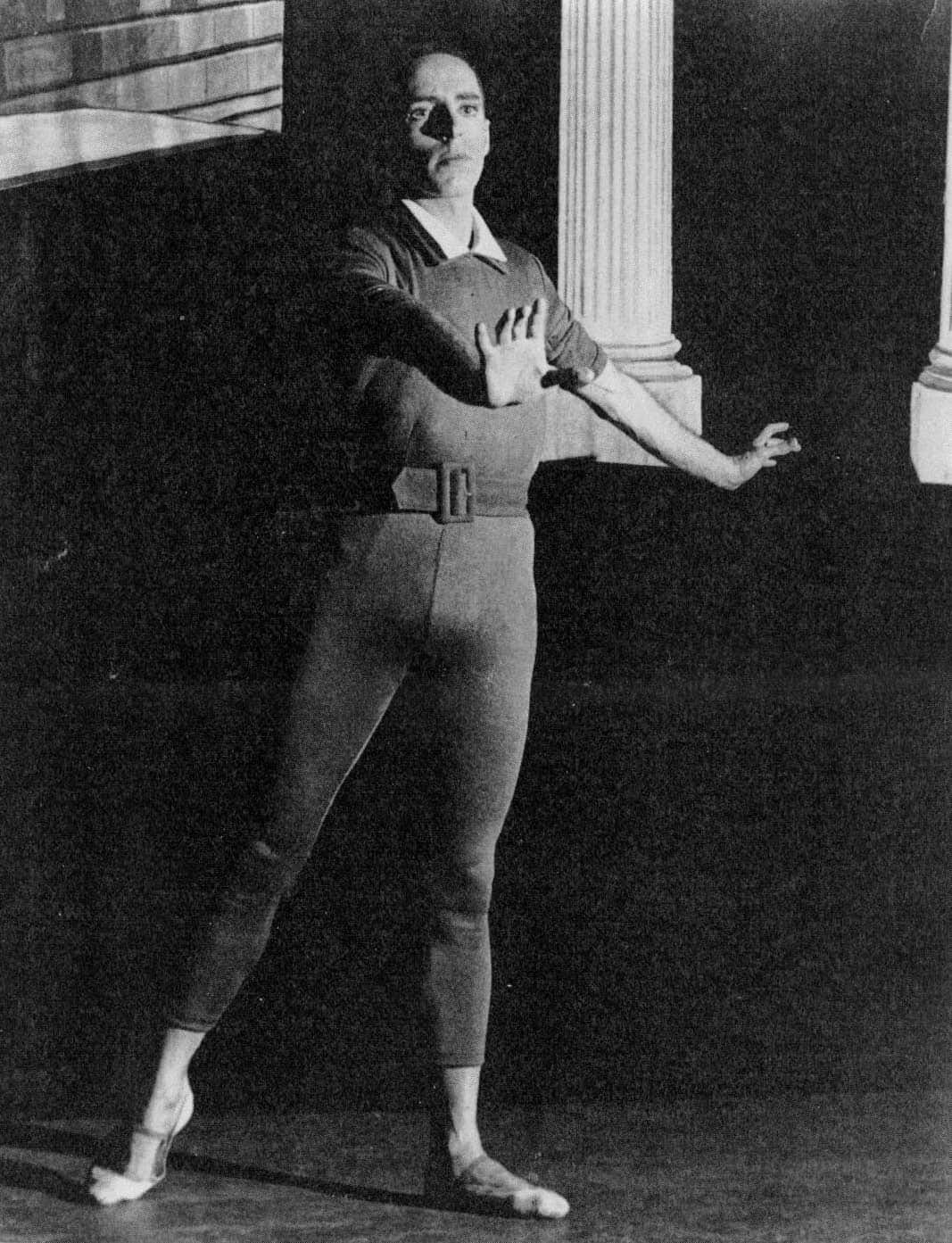

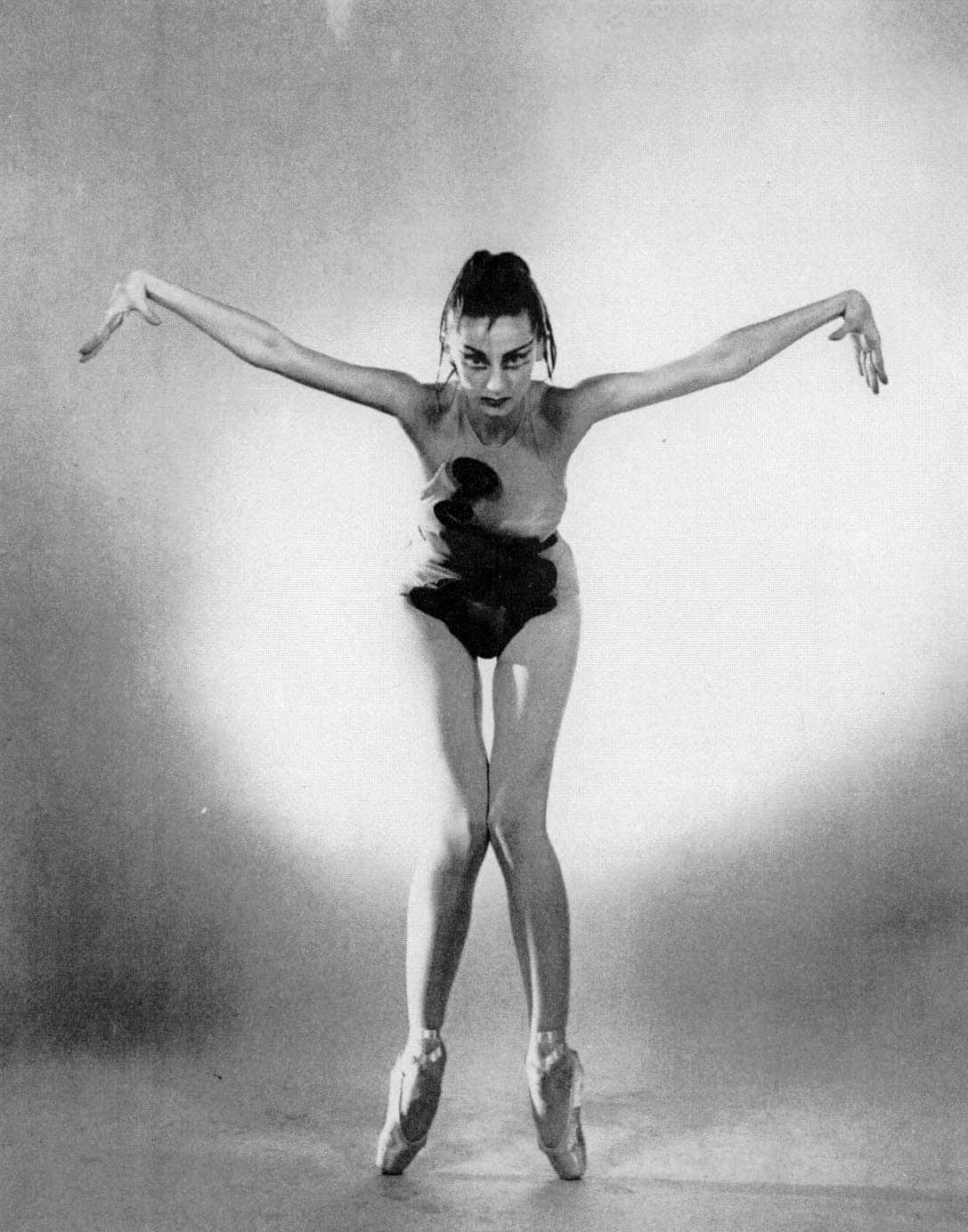

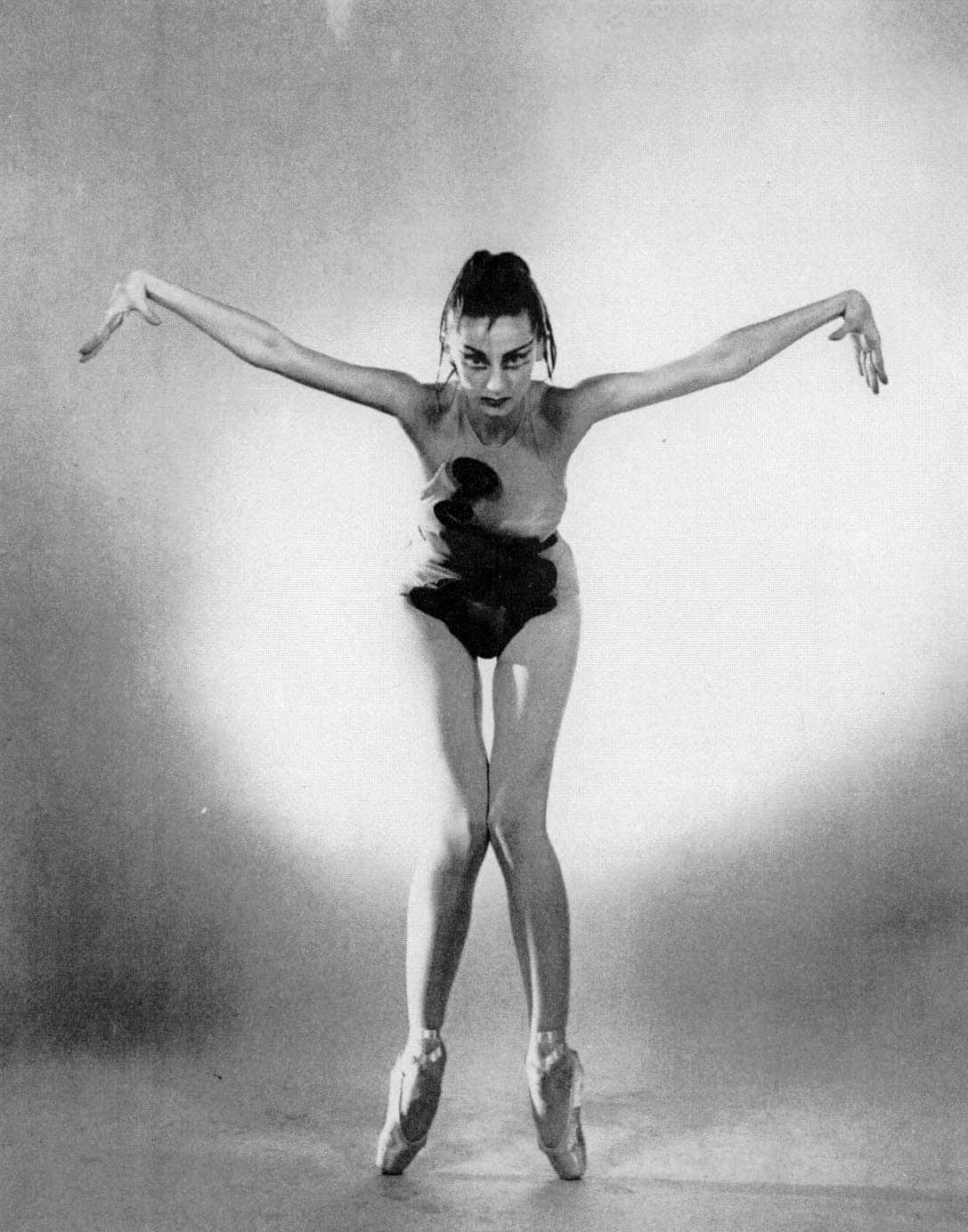

Age of Anxiety: Jerome Robbins, 1950. (Photo uncredited)

|

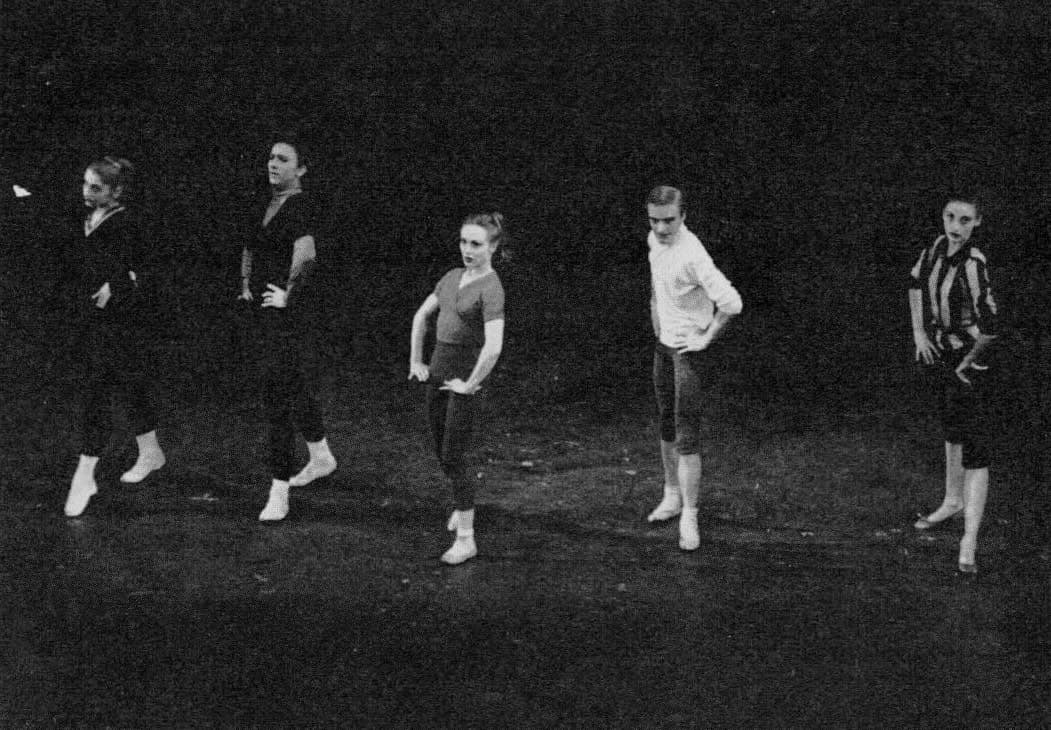

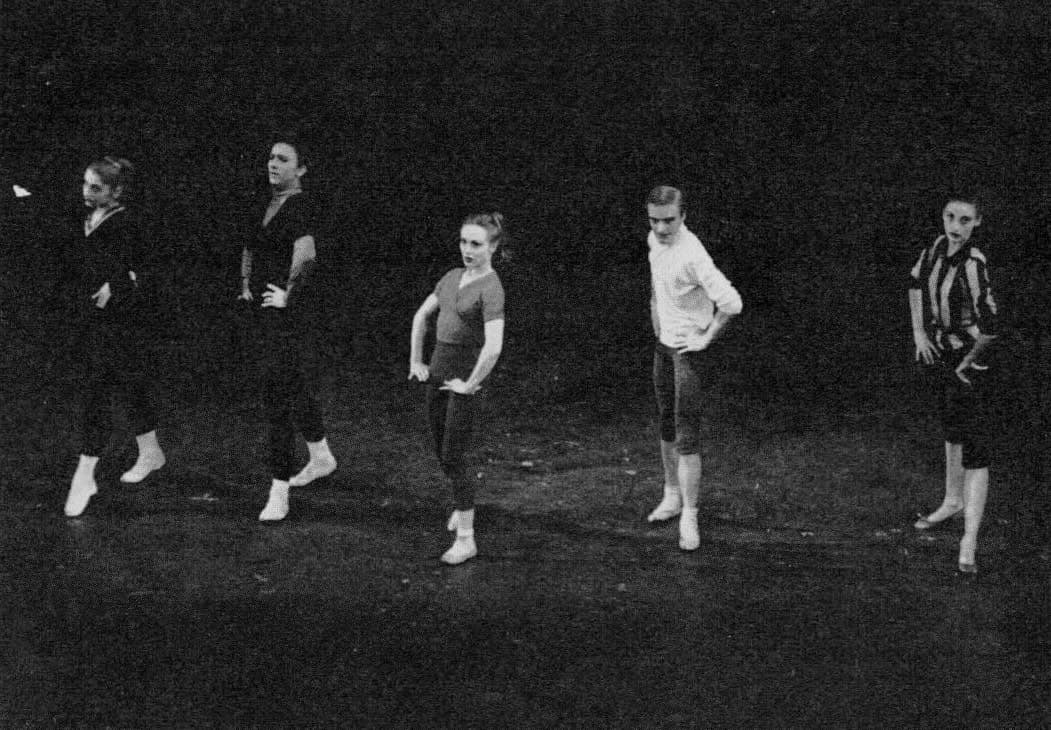

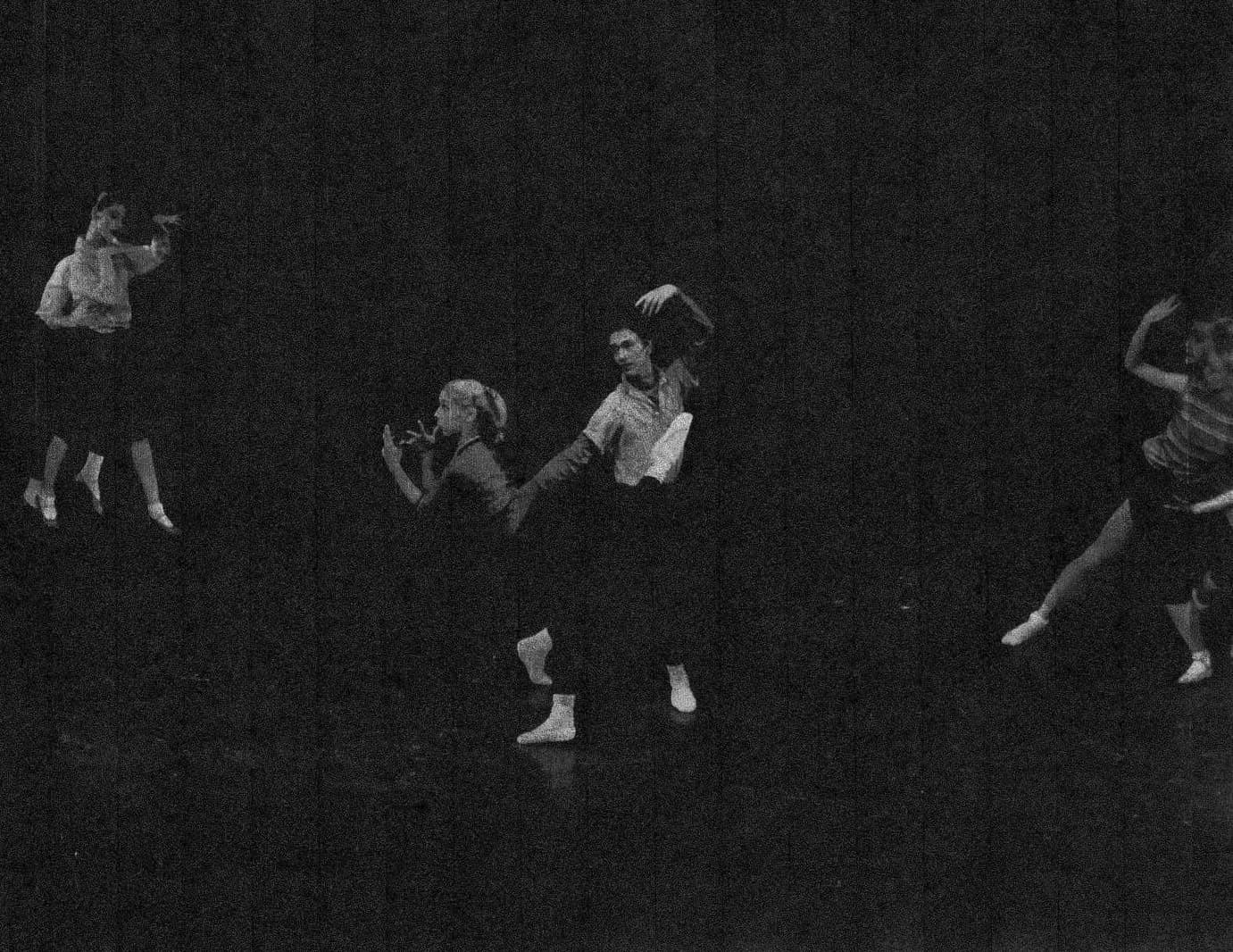

Age of Anxiety: Francisco Moncion, Hugh Laing, Tanaquil Le Clercq, Todd Bolender, 1951. (Walter E. Owen)

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

318 |

| Ballet |

9 |

B9 |

B009 |

Jones Beach |

|

Jurriaan Andriessen |

Berkshire Symphonies [Symphony No. 1 for Orchestra] |

January 1, 1949 |

|

By Jurriaan Andriessen (Berkshire Symphonies [Symphony No. 1 for Orchestra], 1949). |

No |

|

George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

|

Jantzen |

Jean Rosenthal |

|

|

|

|

1,950 |

March 9, 1950 |

|

City Center of Music and Drama |

New York City |

March 9, 1950, City Center of Music and Drama, New York City. |

New York City Ballet |

|

In the repertory: 1950. |

New York City Ballet. In the repertory: 1950. |

First Movement–“Sunday”(Allegro): Melissa Hayden, Beatrice Tompkins, Yvonne Mounsey, Herbert Bliss, Frank Hobi, Audrey Allen, Barbara Bocher, Joan Bonomo, Doris Breckenridge, Arlouine Case, Ninette d’Amboise, Dorothy Dushock, Edwina Fontaine, Jillana, Una Kai, Peggy Karlson, Helen Komarova, Pat McBride, Barbara Milberg, Francesca Mosarra, Janice Nagley, Moira Paul, Ruth Sobotka, Harriet Talbot, Barbara Walczak, Margaret Walker, Tomi Wortham, Robert Barnett, Dick Beard, Val Buttignol, Jacques d’Amboise, Walter Georgov, Brooks Jackson, Shaun O’Brien, Karel Shook, Roy Tobias. Second Movement–“Rescue” (Andante): Tanaquil Le Clercq, Nicholas Magallanes, Helen Komarova, Pat McBride, Dick Beard, Shaun O’Brien. Third Movement–“War with Mosquitoes” (Scherzo): Todd Bolender, William Dollar, Roy Tobias, Doris Breckenridge, Barbara Bocher, Peggy Karlson, Ruth Sobotka, Barbara Walczak, Margaret Walker, Tomi Wortham. Fourth Movement–“Hot Dogs” (Allegro): Maria Tallchief, Jerome Robbins, and the company. |

Leon Barzin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“Jones Beach is a magnificent beach-resort within an hour’s drive of New York City. Enjoyed by millions of New Yorkers, it has become the symbol of popular recreational facilities. The gaiety and exuberance of Jurriaan Andriessen’s new symphony reminded George Balanchine of the vivacious nonsense that takes place among the young people at such a resort, and with Jerome Robbins he arranged dances inspired by the beach-games and swimming.” (This programme note taken from performances given at The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, July 1950.) |

-Jerome Robbins’ first choreographic collaboration with George Balanchine.

-Premiere dedicated to Serge Koussevitsky.

-Music commissioned by the Royal Government of The Netherlands. |

|

|

Jerome Robbins (interviewed by Nancy Reynolds for her book ‘Repertory in Review,’ 1974):

“George [Balanchine] asked if I would help him do the ballet. He said, ‘We’ll do it together.’ And I said ‘Fine. How are we going to do it?’ And we worked it out this way, which was one of the most exciting experiences I’ve had. I was in one room working on one ballet, and he was in another room working on ‘Jones Beach.’ He did about two minutes of the first movement and gave the dancers a break. Then he came into my room and said ‘Okay, now you pick up from where I left off.’ And when the dancers came back again, they ran what they had done, and I just started right there, without any preparation and went on for another two minutes. Then I took a break, and showed him what I had done, and he went on from there.” |

Cecil Smith (Musical America, March 1950):

“A featherweight genre piece, the new work sets forth the trivia of life at the seashore in four sections called Sunday, Rescue, War with Mosquitoes, and Hot Dogs. Most of the ballet is neither very funny nor very attractively provided with movement patterns….Pantomime passages dealing with the attacks of mosquitoes and the consumption of hot dogs hardly constitute landmarks in ballet history.” Frances Herridge (New York Post, March 10, 1950):

“Jones Beach is the gayest and liveliest stretch of dancing in many a year….There is never a doubt as to what is happening on stage, although literal movements are ingeniously translated into stylized dance….The big climax is the beach party with Jerome Robbins and Maria Tallchief to lead the group in some of the hottest ballet jive doing.” Miles Kastendieck (New York Journal-American, March 10, 1950):

“The world premiere of Jones Beach introduced a work as American as hot dogs and as vital as American youth. It is bright and alive, urgent and athletic, obvious and fun.” John Martin (New York Times, March 10, 1950):

“The ballet is credited choreographically to both George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins, and though the idea was perhaps Mr. Balanchine’s to begin with, there are also evidences of Mr. Robbins’ collaboration. It is a gay romp, a piece of vivacious nonsense, so full of people and movement that one is tempted to subtitle it Symphony in Sea….Everything that can happen at a public beach except sunburn pops up sooner or later–yes, practically everything.” Walter Terry (New York Herald Tribune, March 10, 1950):

“There are thin spots here and there and some passages which appear to have been hastily, even frantically, contrived but they are not numerous and the recreational aspects together with the carefree attitudes of a day at the beach are pleasantly, amusingly conveyed….The ballet is divided into four movements: Sunday, Rescue, War with Mosquitoes, and Hot Dogs….Mr. Robbins and Miss Tallchief were on hand for the finale, which I am inclined to believe represented Mr. Robbins’s major choreographic contribution to the ballet, and they mimed and danced their parts with wit and gusto.” |

Jones Beach rehearsal: Jerome Robbins and Maria Tallchief, 1952. (Photo uncredited)

|

Jones Beach: Nicholas Magallanes, Tanaquil Le Clercq, 1950. (Photo uncredited)

|

Jones Beach: Tanaquil Le Clercq, Nicholas Magallanes, 1950. (George Platt Lynes)

|

Jones Beach: Jerome Robbins, Maria Tallchief, 1950. (George Platt Lynes)

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

319 |

| Ballet |

10 |

B10 |

B010 |

The Cage |

|

Igor Stravinsky |

Concerto in D for String Orchestra [“Basler”] |

January 1, 1946 |

|

By Igor Stravinsky (Concerto in D for String Orchestra [“Basler”], 1946). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

Jean Rosenthal |

|

Ruth Sobotka |

Jean Rosenthal |

|

|

|

|

1,951 |

June 14, 1951 |

|

City Center of Music and Drama |

New York City |

June 14, 1951, City Center of Music and Drama, New York City. |

New York City Ballet |

|

In the repertory: 1951-55, 1957-59, 1961-65, 1969-74, 1976-82, 1984-85, 1987-91, 1994-95, 1997-2000, 2003-06, 2008. |

New York City Ballet. In the repertory: 1951-55, 1957-59, 1961-65, 1969-74, 1976-82, 1984-85, 1987-91, 1994-95, 1997-2000, 2003-06, 2008. |

The Novice: Nora Kaye. The Queen: Yvonne Mounsey. The Intruders: Nicholas Magallanes, Michael Maule. The Group: Constance Baker, Barbara Bocher, Arlouine Case, Edwina Fontaine, Jillana, Una Kai, Irene Larsson, Barbara Milberg, Marsha Reynolds, Patricia Savoia, Ruth Sobotka, Tomi Wortham. |

Leon Barzin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“There occurs in certain forms of insect and animal life, and even in our own mythology, the phenomenon of the female of the species considering the male as prey. The mantis devours her partner immediately after mating; the female spider kills the male unless he attacks her first and subdues her preying instincts; the Greek Amazons established a cult completely apart from men except for procreation, crippling or destroying their male offspring. The ballet, derived from these sources, concerns such a race or cult…the rites and blood instincts.” |

-The intended original title for the ballet (as revealed in promotional material) was The Amazons. |

1961, Ballets: U.S.A.; 1984, Pacific Northwest Ballet; 1996, Birmingham Royal Ballet; 1998, San Francisco Ballet; 2001, Stuttgart Ballet; 2001, Dutch National Ballet, Paris Opera Ballet. |

|

Jerome Robbins (Dance Magazine, August 1955):

“It’s about a tribe of women. A novice is to be initiated. She doesn’t yet know her duties as a member of the tribe nor is she aware of her innate instincts. She falls in love with a man and mates with him. But the rules of the tribe demand his death. She refuses to kill him but when his blood actually flows, her animal instincts are aroused and she rushes forward to complete the sacrifice. Her affection yields to her tribal instinct.” Jerome Robbins (interviewed by Margaret Mercer for radio station WQXR [New York City], May 19, 1990):

“I had a recording of ‘Apollo,’ and the flip side was ‘Concerto in D for Strings’….The music had an appealing dramatic nature.. I was studying Greek myths and I came across the story of the Amazons and how one of them fell in l ove with the Greeks who happened to come there, and went against the tribe. That got me thinking….I thought about how the story might fit ‘The Cage’….and then I started it….and I did more research about women’s sects, and the phenomenon of insect life…” |

Miles Kastendieck (New York Journal-American, June 15, 1951):

“Neither the subject nor the ballet is pretty. Through his individuality of style, Robbins has accentuated the preying instinct with sure regular strokes. The atmosphere is charged: the action is tense. Given a dynamic crisp performance, the effect is powerful, even horrifying.” John Martin (New York Times, June 15, 1951):

“It is easily the most important work of the season….It is an angry, sparse, unsparing piece, decadent in its concern with misogyny and its contempt for procreation….Its characters are insects, it is without heart or conscience, and its opinion of the human race is not a high one. But in spite of the potency of its negations, it is a tremendous little work, with the mark of genius upon it….The movement is wonderfully conceived, both in its relation to the impulses of the body and in the tautness of its phrase.” Robert Sylvester (New York Daily News, June 15, 1951):

“The choreography proves conclusively enough that the way the female destroys the male is by…er…uh…well, maybe you better see it yourself….All in all, The Cage can be accepted as Robbins’ most typical ballet for Nora Kaye since Facsimile.” Walter Terry (New York Herald Tribune, June 15, 1951):

“Mr. Robbins’ ballet does not specify the insect, the animal or the human, although attributes of each are indicated in the movements. Rather is his work a primitive ceremonial which celebrates with a certain aloof frenzy this terrifying digression from the accepted social pattern of modern man….Mr. Robbins, in this The Cage, has created a startling, unpleasant but wholly absorbing theater piece. The movements, with few exceptions, are not only pertinent to the theme but they drive its meaning to the fore with passion and clarity.” Douglas Watt (New Yorker, June 23, 1951):

“The Cage is a melodramatic novelty, and as such it’s rather effective. Its most novel aspect is the use of Igor Stravinsky’s String Concerto in D for its music. This was a delightful idea, for the nervous and rhythmical picking and sawing of the strings, especially in the final movements, is amusingly suggestive of insect activity–a fact I don’t suppose occurred to anybody before Robbins….A sportive new work, on the whole.” Nik Krevitsky (Dance Observer, November 1951):

“Jerome Robbins’ The Cage is a wild, frenzied, violent, unrelieved rite….In this work, which requires more analysis than we have room for at this writing, Miss Kaye is superb in a grotesque movement pattern, exciting for its primitive abandon and archaic movements.” |

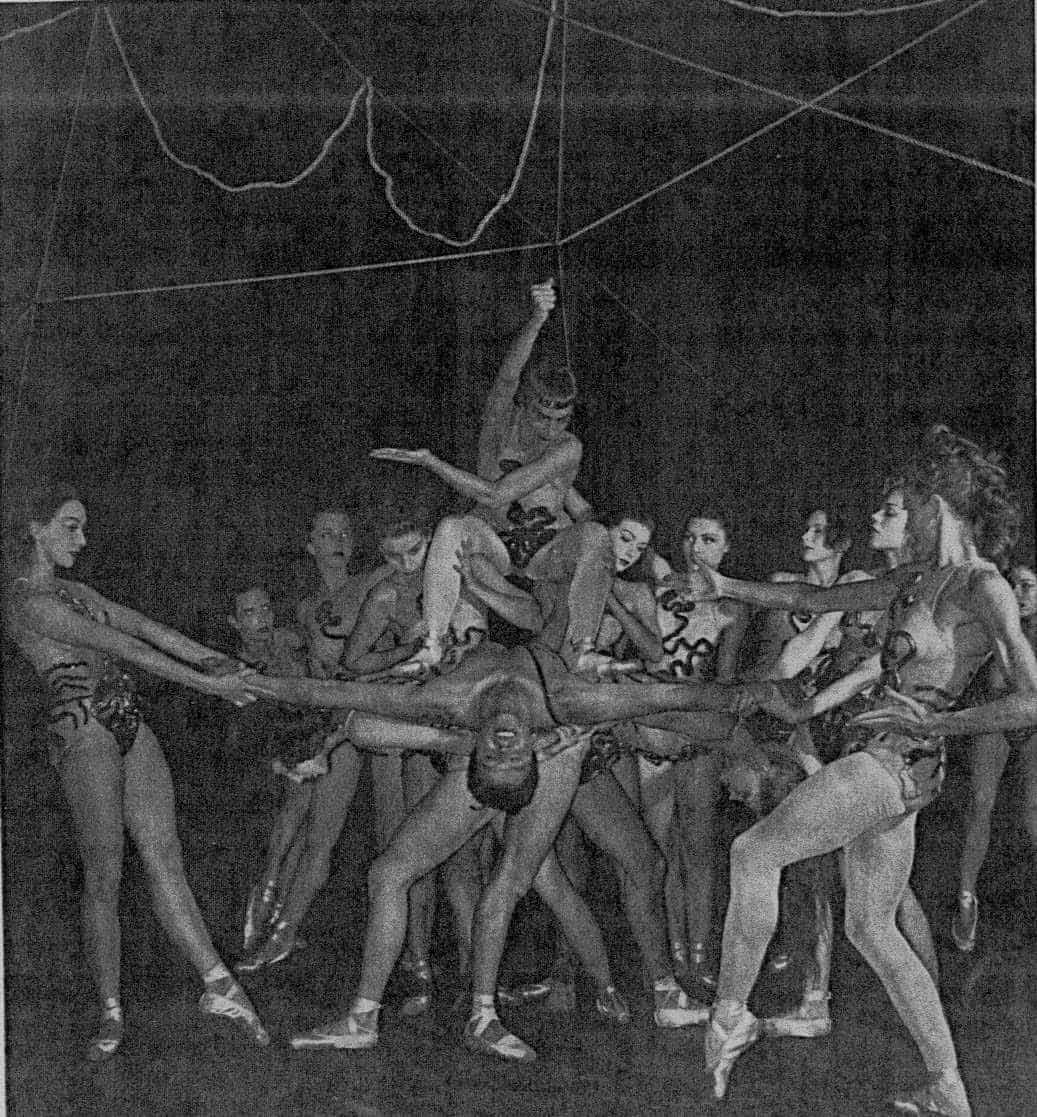

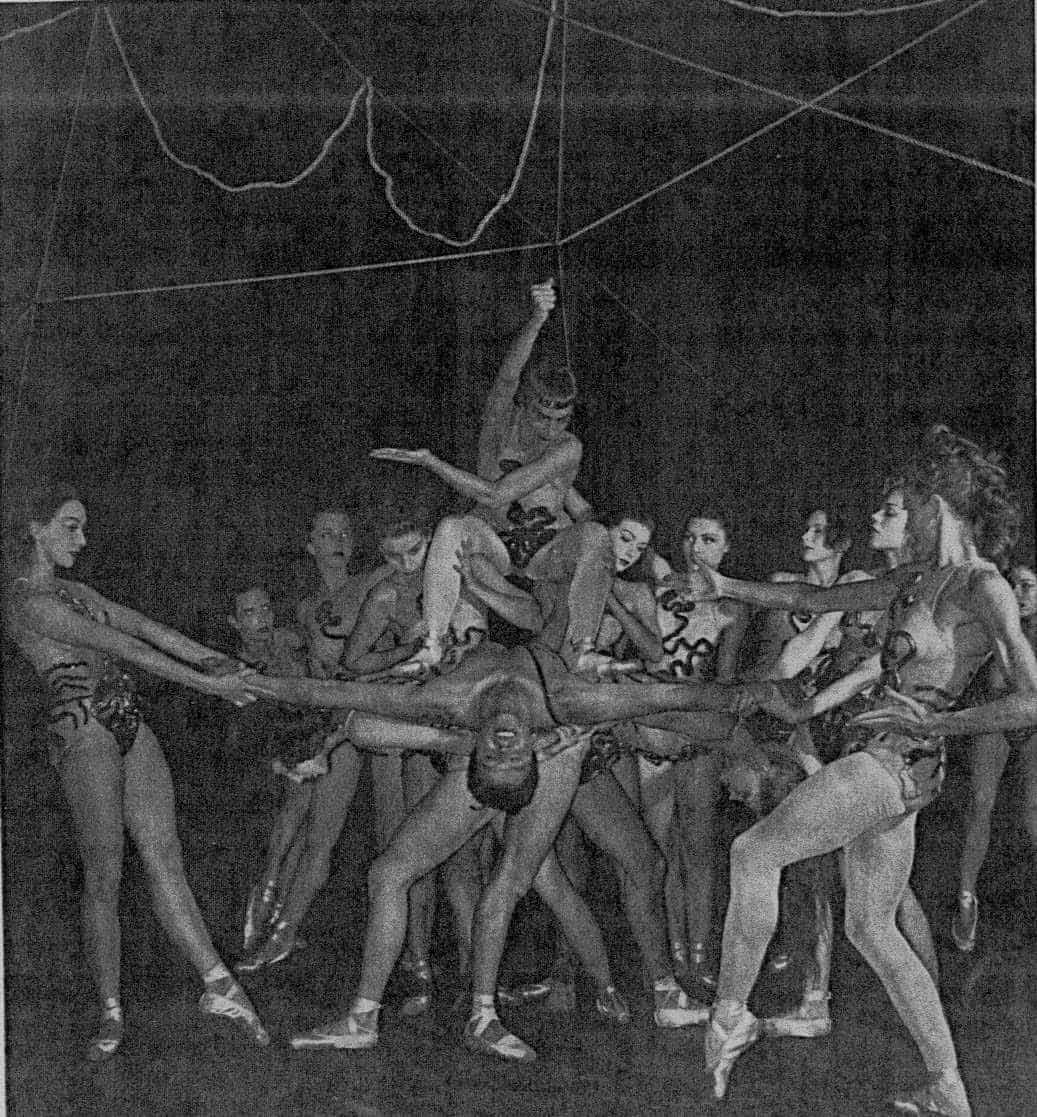

The Cage: Yvonne Mounsey, Michael Maule, 1951. (Melton-Pippin)

|

The Cage: Nora Kaye, Michael Maule, 1951. (Walter E. Owen)

|

The Cage: Tanaquil Le Clercq, 1951. (Photo uncredited)

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

320 |

| Ballet |

11 |

B11 |

B011 |

The Pied Piper |

|

Aaron Copland |

Concerto for Clarinet, Strings, Harp, and Piano |

June 30, 1947 |

|

By Aaron Copland (Concerto for Clarinet, Strings, Harp, and Piano, 1947). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

|

|

Jean Rosenthal |

|

|

|

|

1,952 |

December 4, 1951 |

|

City Center of Music and Dance |

New York City |

December 4, 1951, City Center of Music and Dance, New York City. |

New York City Ballet |

|

In the repertory: 1951-55, 1957-59. |

New York City Ballet. In the repertory: 1951-55, 1957-59. |

Diana Adams, Nicholas Magallanes, Jillana, Roy Tobias, Janet Reed, Todd Bolender, Melissa Hayden, Herbert Bliss, Tanaquil Le Clercq, Jerome Robbins, Constance Baker, Barbara Bocher, Doris Breckenridge, Edith Brozak, Arlouine Case, Ninette d’Amboise, Una Kai, Irene Larsson, Marilyn Poudrier, Marsha Reynolds, Kaye Sargent, Patricia Savoia, Ruth Sobotka, Gloria Vauges, Barbara Walczak, Tomi Wortham, Alan Baker, Robert Barnett, Jacques d’Amboise, Walter Georgov, Brooks Jackson, Shaun O’Brien, Stanley Zompakos. |

Leon Barzin |

|

Edmund Wall (The Piper) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“The ballet has nothing to do with the famous Pied Piper of Hamelin and refers instead to the clarinet soloist.” |

|

|

|

Jerome Robbins (interviewed by Nancy Reynolds for her book ‘Repertory in Review,’ 1974): “I liked the music…I keep finding that this ballet turned out to be a germinal work for a lot of Broadway choreographers. I kept seeing it pop up in other shows, many of those ideas…It was fun to do. I enjoyed it very much.” |

Frances Herridge (New York Post, December 5, 1951): “No symbolism, no message, just a wonderful time with the infectious rhythms of Aaron Copland’s ‘Concerto for Clarinet and string Orchestra’….It is clowning in modern jazz. But it’s a good deal more. Its development from nothing, its superb climax, its interplay of groups, make it a significant art work.” Miles Kastendieck (New York Journal-American, December 5, 1951): “Jerome Robbins cut loose at the City Center last night. The world premiere of The Pied Piper found him with his hair down, his tongue out, and his talent rampant. In his way he has created a little masterpiece of fun and foolery, freedom and fashion. The work scored an instantaneous hit….If ever there was a demonstration of what music could do to people, this is it.” John Martin (New York Times, December 5, 1951): “There is no doubt about it, the boy has talent! This is a larger work in the same vein as his ‘Interplay,’ putting together basic elements of both the academic ballet and jazz, with a slightly rambunctious sense of play as the fusing agent. If classicism does not imply too lofty a tone, this is actually a classic idiom in its own terms, and a very responsive one as Robbins employs it….Much of it is hilariously funny, full of absurd and impish invention.” Arthur Pollock (Compass, December 5, 1951): “If, having seen some of the modern ballets that look childish but seem to want to be accepted as profound, you guess that in this one troops of grown-up dancers run around pretending to be rats and infants, you will be guessing wrong. It is simply a ballet in which a lot of animated girls and boys can’t help dancing when they hear a man play Aaron Copland on his clarinet….It is a gem of a ballet, quick and brilliant and comical.” Robert Sylvester (New York Daily News, December 5, 1951): “With it, Robbins reaffirms all the talent and imagination he always shows on Broadway….The new Robbins work has touches of Our Town, touches of Orson Welles, and touches of jazz….At one point Robbins manages to have everybody doing a Charleston, at another he has everybody on the floor, and at still another he has them just jumping up and down for laughs. The whole thing adds up to solid ballet fun.” Walter Terry (New York Herald Tribune, December 5, 1951): “The real worker of magic is Mr. Robbins, whose choreographic inventions, fresh and impulsive, bring music and dancing together in happy association….The movements Mr. Robbins has created actually belong in that great area of dance we call kinetic pantomime….Music is the stimulus but the resulting dance is almost wholly kinetic in its projecting of lyrical beauties and boisterous humors. Some of the action is balletic, but the greater part of it is highly individualistic….Because there is neither a trite movement nor a slothful moment in it, The Pied Piper is constantly surprising, continually refreshing.” Douglas Watt (New Yorker, December 15, 1951): “This brilliant and contagious dance work was presented for the first time last week, with Robbins himself in one of the main parts….The whole production made it seem as if Walt Disney had finally succeeded in creating people.” Nik Krevitsky (Dance Observer, January 1952): “In typical Robbins fashion, this work proved to be fresh, novel, and full of invention; the basic idea itself being a delightful surprise, having little or nothing to do with the familiar legend of Hamelin. If one can bring the far-fetched notion of a happy gang of young people being kinesthetically hypnotized by a clarinetist into the context of the original Pied Piper there might seem to be some relationship….What he has done with the material is completely new, completely engaging, and alive from start to finish.” Cecil Smith (Musical America, January 1, 1952): “Like ‘Interplay’–but, in its initial form, considerably less successful–The Pied Piper is an essay in formal informality….The whole ballet seems thrown together hastily from Mr. Robbins’ stockpile of used ideas, with a minimal number of new ones added in….The short-phrased agitations of Mr. Robbins’ dance figures do not accord with the large intellectual span Mr. Copland seeks to achieve by his studied and architectural deployment of the musical figures.” Edwin Denby (Ballet, August 1952): “I was mortified to see them dancing still in the style of Swan Lake, dancing the piece wrong and looking as square as a covey of mature suburbanites down in the rumpus room. All but one dancer, Tanaquil Le Clercq, who does the style right, and looks witty and graceful and adolescent as they all so easily might have by nature. The piece has a Robbins-built surefire finale, and the public doesn’t even guess at the groovy grace it is missing.” |

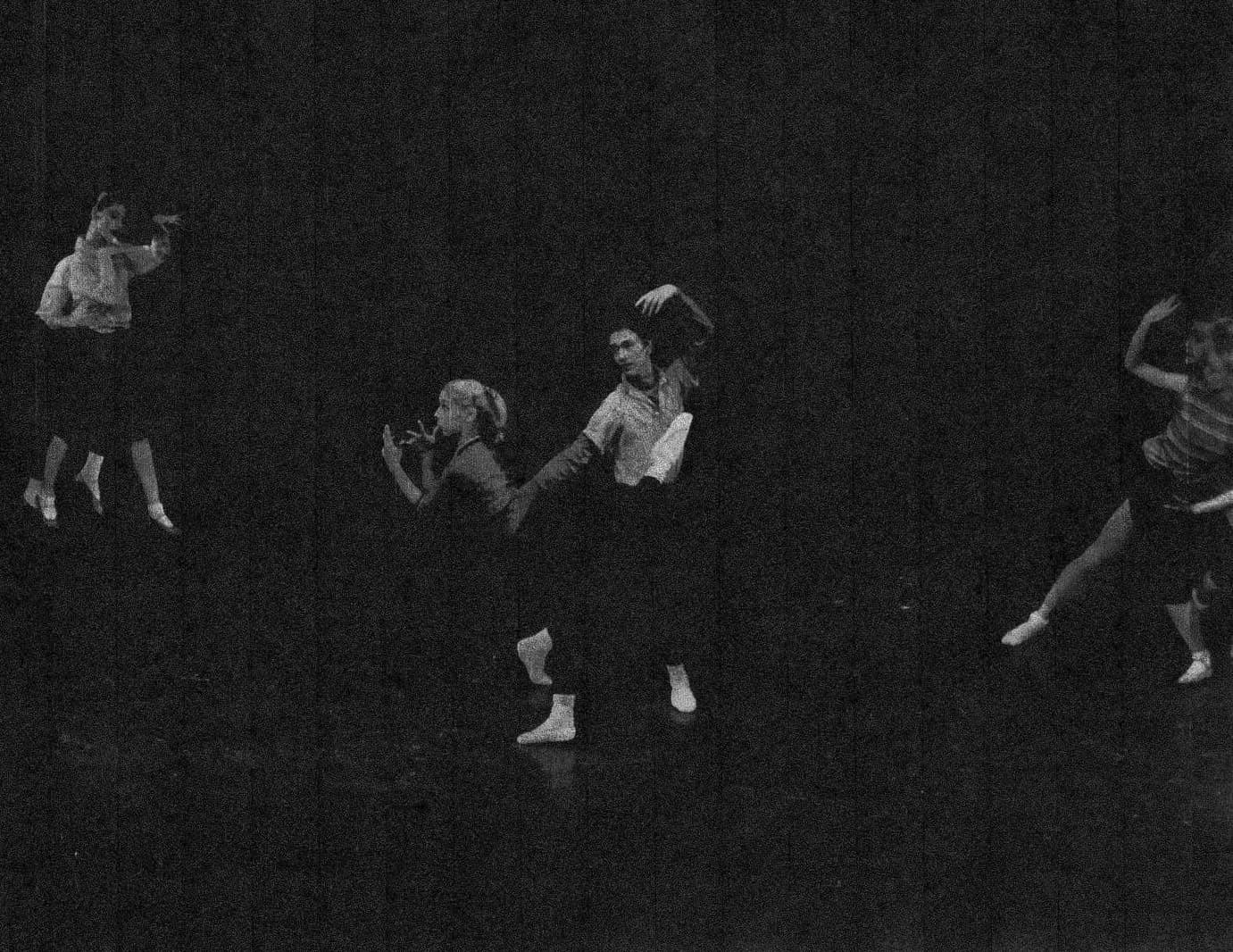

The Pied Piper: Barbara Bocher, Todd Bolender, Janet Reed, Robert Bennett, Tanaquil Le Clercq, 1951. (Fred Fehl)

|

The Pied Piper: 1951. (Fred Fehl)

|

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

321 |

| Ballet |

12 |

B12 |

B012 |

Ballade |

|

Claude Debussy |

Six Épigraphes Antiques, 1915 [orchestrated by Ernest Ansermet, 1932]; and Syrinx for solo flute |

June 30, 1912 |

|

By Claude Debussy (Six Épigraphes Antiques, 1915 [orchestrated by Ernest Ansermet, 1932]; and Syrinx for solo flute, 1912). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

Boris Aronson |

Boris Aronson |

Jean Rosenthal |

|

|

|

|

1,952 |

February 14, 1952 |

|

City Center of Music and Drama |

New York City |

February 14, 1952, City Center of Music and Drama, New York City. |

New York City Ballet |

|

In the repertory: 1952. |

New York City Ballet. In the repertory: 1952. |

Tanaquil Le Clercq, Nora Kaye, Janet Reed, Roy Tobias, Louis Johnson (guest), Robert Barnett, John Mandia, Brooks Jackson. |

|

|

|

Frances Blaisdell |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“A musical composition of poetic character…a dancing song, a poem of unknown authorship which recounts a legendary or traditional event and passes from one generation to another…”-Webster’s Dictionary, on “ballade” and “ballad.” |

|

|

|

Jerome Robbins (interviewed by Nancy Reynolds for her book ‘Repertory in Review,’ 1974): “It is about what happens to roles when people aren’t dancing them. There’s that Petrouchka costume waiting on a rack somewhere. Or there’s the role in limbo. Everyone talks about Petrouchka, but it’s only when someone gets into that role that the role comes to life and exists again. Then when that person stops, the role collapses. Roles are endowed by whatever artist it is that happens to dance them. To me, that’s what’s underneath it all. It’s the state of hibernation until something happens.” |

Frances Herridge (New York Post, February 15, 1952): “The atmosphere of informal fantasy quite obviously cloaks Robbins’ vision of life, and it is a sad, lonely one. But what the characters stand for specifically in the ballet is uncertain….Whatever Robbins’ meaning, the ballet has a stirring end even though elusive.” John Martin (New York Times, February 15, 1952): “Mr. Robbins has given us a Pierrot and Columbine piece that is cute, cloying and self-conscious. It has falling snow, toy balloons, and all the clichés of the degenerated nineteenth-century form of the Italian comedy….Perhaps Mr. Robbins may have had some idea of drawing tragic, or poignant, overtones from their situation, but his sentimental approach to both the music and the movement would tend to contradict such a theory….Oh well; after all, it is he who has given us Age of Anxiety and The Cage, and it is up to us this morning to think on these things.” Robert Sylvester (New York Daily News, February 15, 1952): “Jerome Robbins’ new Ballade ballet is one of the young maestro’s dreamy epics which isn’t quite slow enough to put you to sleep and not nearly lively enough to keep you anywhere near the edge of your chair. It has meaning, no doubt.” Walter Terry (New York Herald Tribune, February 15, 1952): “Ballade is a sweet and touching reminder of wistful feelings close to the heart of each of us. At its close, one does not wish to applaud, for the noise would jar the sharing of a dream….Sweet and tender and nostalgic, but what does it recall? Nothing very specific, admittedly. Robbins has created fresh, unforced, wonderfully simple movements which never actually lead to a neat, tidy, and thoroughly dead resolution. But this might be the true dance symbol of youth, eager to explore many exciting avenues but not interested in arriving at a final destination too soon.” Albert J. Elias (Compass, February 17, 1952): “Mr. Robbins left me completely up in the air on Thursday evening with Ballade, his new ballet….What little pretty dance there is can hardly be taken for its face value when dancers fall into patterns that only make one ask, ‘What is she doing? What is he doing?’” Douglas Watt (New Yorker, February 23, 1952): “Set to Debussy’s ‘Six Epigraphes Antiques,’ it is a precious little thing with a theatrical start and finish and nothing you can put your finger on in between….The dancing is almost uniformly tortured and unattractive, and both costumes and makeup are unflattering to everybody. The balloons are very pretty, however.” Robert Sabin (Dance Magazine, March 1952): “It is a single and serious conception, and although I should be hard put to it to support my judgement with intellectual arguments, it strikes me as a genuine success.” Rosalyn Krokover (Musical Courier, March 11, 1952): “There were chairs, balloons, a sawdust heart and little of interest choreographically to hold one’s attention. Many of the ideas were derivative, and there was little dance invention. Everyone is entitled to an occasional off-night; and this was definitely Robbins.’” Anatole Chujoy, (Dance News, April 1952): “This is a ballet that absolutely demands a program note. The curtain rises on a dim stage peopled by half a dozen figures huddled on chairs against a backcloth. Snow is falling heavily, adding to the melancholy of the scene. A balloon-vendor enters, places a balloon in each inert hand, and walks away. The balloons endow the puppets with life, and each rises to his or her feet with the pull of the balloon….This is a striking opening, but after that Robbins seems completely at a loss.” Doris Hering (Dance Magazine, May 1952): “Jerome Robbins’ Ballade, despite its outward poetic trappings, is not a poetic work. It is a feeble bit of misanthropy whose cute theatrical tricks titillate rather than move.” Edwin Denby (Ballet, August 1952): “I liked it because at the end one girl at least discovers a way out of the trap that Robbins evidently intended to catch all of them in; she wasn’t sure she wanted to get out, but it was clear she could if she chose. I liked the musicality of Ballade very much. And the Aronson décor too, so Debussy and real peculiar.” |

|

|

|

|

|

June 9, 2023 07:46 PM |

|

74.75.80.50 |

322 |

| Ballet |

13 |

B13 |

B013 |

Afternoon of a Faun |

|

Claude Debussy |

Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un Faune |

January 1, 1892 |

-94 |

By Claude Debussy (Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un Faune, 1892-94). |

No |

|

Jerome Robbins |

|

|

|

Jean Rosenthal |

Irene Sharaff |

Jean Rosenthal |

|

|

|

|

1,953 |

May 14, 1953 |

|

City Center of Music and Drama |

New York City |

May 14, 1953, City Center of Music and Drama, New York City. |

New York City Ballet |

|

In the repertory: 1953-65, 1968-81, 1983-84, 1987-92, 1994-95, 1998-2008 |

New York City Ballet. In the repertory: 1953-65, 1968-81, 1983-84, 1987-92, 1994-95, 1998-2008 |

Tanaquil Le Clercq, Francisco Moncion. |

Leon Barzin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

|

“Debussy’s music, Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un Faune, was composed between 1892 and 1894. It was inspired by a poem of Mallarmé’s which was begun in 1865, supposedly for the stage, the final version of which appeared in 1876. The poem describes the reveries of a faun around a real or imagined encounter with nymphs. In 1912 Nijinsky presented his famous ballet, drawing his ideas from both the music and the poem among other sources. This pas de deux is a variation on these themes.” |

-The ballet appeared among ten pas de deux comprising the ballet Celebration [B37]. |

1958, Ballets: U.S.A.; 1966, Royal Danish Ballet; 1971, Dance Theatre of Harlem, Royal Ballet; 1972, Royal Danish Ballet; 1974, Paris Opera Ballet; 1975, Hamburg Ballet; 1976, San Francisco Ballet; 1977, Batsheva Dance Company of Israel, National Ballet of Canada; 1978, Australian Ballet, Denver Civic Ballet; 1980, Teatro Alla Scala, Zürich Ballet; 1984, Kansas City Ballet; 1991, Star Dancers Ballet; 1998, Stuttgart Ballet; 1999, Suzanne Farrell Ballet; 2000, Bolshoi Ballet; 2002, Ballet West; 2005, American Ballet Theatre, Miami City Ballet; 2006, Scottish Ballet; 2008, Houston Ballet, Leipzig Ballet, Oregon Ballet Theatre. |

|

Jerome Robbins (interviewed by Nancy Reynolds for her book ‘Repertory in Review,’ 1974): “‘Faun’ came out of a couple of sources. First of all, my fascination with the original....Then one day in class, little Eddie Villella, who was standing next to me and who was just a kid, suddenly began to stretch his body in a very odd way–almost like he was trying to get something out of it. And I thought of how animalistic it was....And then another time I walked into a rehearsal studio and Willie Johnson was practicing the ‘Swan Lake’ adagio with some student girl. They were watching themselves in the mirror, and I was struck by the way they were watching that couple over there doing a love dance, and totally unaware of the proximity and possible sexuality of their physical encounters. The combination of all those things finally put the ballet into my head.” |

Louis Biancolli (New York World-Telegram and Sun, May 15, 1953):

“It was beautiful and tender, poetic and restrained, and highly imaginative. I wouldn’t be at all astonished if it is remembered as Mr. Robbins’ most artistic gift to ballet….Mr. Robbins has taken the faun out of Greek mythology and put him to work in a dance studio….One masterly stroke was the added illusion that the audience was actually serving as the fourth wall of the dance studio–that is the wall with the mirrors.” Frances Herridge (New York Post, May 15, 1953):